You may have wandered around the 4th floor of Exley Science Center, looking for your class in room 405, and caught a glance of a bison. And if you had just awoken from a short sleep the night before, you may have even thought that this bison was one of your sleep deprivation-induced hallucinations. Fear not: there really is a taxidermic bison on the 4th floor of Exley in Wesleyan’s Joe Webb Peoples Museum of Natural History, and he goes by the name Greg! In 1875, Georg Brown Goode, an ichthyologist and Wesleyan alum (year of 1870), received Greg (who had been stuffed in Carson City, NV) from John Wallace. G. Brown Goode was the son-in-law of Orange Judd, who funded the building of Judd Hall in which the Wesleyan Museum was originally based, and he was the first Curator of the Wesleyan Museum at its establishment in 1871.

You can visit Greg at Wesleyan University’s Joe Webb Peoples Museum of Natural History.

Greg at his former residence in the Wesleyan Museum in Judd Hall back in the summer of 1957. Image from Wesleyan University Library, Special Collections & Archives.

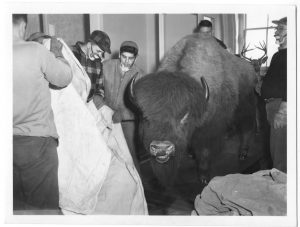

Greg being moved after the dissolution of Wesleyan Museum in Judd Hall, 1957.

Image from Wesleyan University Library, Special Collections & Archives.

Greg is an American bison (Bison bison), the U.S. national mammal and the largest terrestrial animal in North America. Male bison weigh up to 2,000 pounds, whereas females weigh up to 1,000 pounds.[1] Despite their size, bison can run at speeds over 30 miles per hour—which is why Yellowstone National Park warns visitors to stay at least 25 yards away from all wild bison.[2] In his old age, Greg no longer quite reaches those speeds, so feel free to get a bit closer! During Greg’s time at Wesleyan, American Bison went from becoming virtually extinct in the wild to having their population rebound in what is considered one of the greatest conservation success stories of all time.

Scientists estimate that there were 30 to 60 million bison living in the continent when the first European settlers arrived in North America, ranging all the way from northern Canada to northern Mexico, and from western New York to eastern Washington.[3] Bison were commonly referred to as buffalo by European explorers due to their perceived resemblance of Asian and African buffalo. As Euro-Americans began to settle westward, they changed the Bison’s native grassland habitat through plowing and farming, as well as introducing domestic cattle, which brought diseases and competition for grazing. Farmers and ranchers began killing bison to make room for their animals. In addition, as native American tribes acquired horses and guns, they began to kill bison in larger numbers than before. Some U.S. soldiers even killed bison to spite their native American enemies who depended on the animals for food and clothing. Western railroads greatly accelerated the decimation of the American bison by bringing hunters who would shoot the animals out of the open windows of moving trains. The bison were not only killed for sport, but also for their skin, bones (used in making fertilizer)[4], and tongues (a culinary delicacy).[5]

Had it not been for a few private individuals and government action, the American bison would be extinct today. In 1884 there were only 325 out of the many millions bison left in the wild, including 25 in Yellowstone National Park. Congress finally tasked the U.S. Army with enforcing laws prohibiting the killing of any birds or animals in Yellowstone.[6] Congress’s efforts proved successful—as of July 2015, Yellowstone’s bison population is estimated at 4,900 individuals. Private organizations also helped save the bison population. In 1905, Teddy Roosevelt formed the American Bison Society with zoologist William Hornaday, with the aim to start a breeding program at the New York City Zoo (Bronx Zoo today). By 1913, the American Bison Society had enough bison to restore a free-ranging herd to Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota, and this herd have helped reestablish other herds across the United States and Mexico.[7] Restoring bison herds is not only an enormous victory for the U.S. national mammal, but also for the whole grassland ecosystem, because the unique spatial and temporal complexities of bison grazing are critical to the successful maintenance of biotic diversity in grasslands.[8]

Bison in private herds in part account for the rebound in the bison population of North America. In the 1870s, when the bison population was dwindling, people began to realize that owning bison could be profitable. Ranchers started collecting the few remaining bison scattered across the prairies to breed them in private herds.[9] It is estimated that by the year 2000 at least 250,000 bison were living in private herds, and 92,000 of these bison were raised for meat. Bison can process North American grasses more efficiently than cattle, and their meat contains less fat and cholesterol, making it an attractive option for human carnivores.[10]

According to Dr. James Derr, Professor of veterinary pathobiology, most bison alive today are genetically different from their wild ancestors. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the ranchers who owned much of the remaining bison population bred their bison with cattle to try to create better animals for meat. It is believed that only about 1.6 percent of today’s bison population is not hybridized.[11] Wesleyan’s Greg dates back to the time severely declining numbers of bison, and represents the original American bison before hybridization.

Some of Greg’s favorite puns. Illustrations by Melissa McKee.

By Melissa McKee

For more information check out

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/harp/0606.html?mcubz=2

[1] U.S. Department of the Interior, 15 facts about our national mammal: the American bison.

[2] Portman, J., 2011, The great American bison: PBS.

[3] Portman, J., 2011, The great American bison: PBS.

[4] U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 2014, Time line of the American bison: National Bison Range Wildlife Refuge Complex.

[5] Winkler, P., 2014, In the beginning, bison: Smithsonian National Zoological Park Conservation Biology Institute.

[6] U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 2014, Time line of the American bison: National Bison Range Wildlife Refuge Complex.

[7] U.S. Department of the Interior, 15 facts about our national mammal: the American bison.

[8] Knapp, A. K., Blair, J. M., Briggs, J. M., Collins, S. L., Hartnett, D. C., Johnson, L. C., and Towne, E. G., 1999, The keystone role of bison in North American tallgrass prairie: Bison increase habitat heterogeneity and alter a broad array of plant, community, and ecosystem processes: BioScience, v. 49, p. 39-50.

[9] Polziehn, R. O., Strobeck, C., Sheraton, J., and Beech, R., 1995, Bovine mtDNA discovered in North American bison populations: Conservation Biology, v. 9, p. 1638-1643.

[10] Portman, J., 2011, The great American bison: PBS.

[11] Portman, J., 2011, The great American bison: PBS.