Our Deinotherium giganteum (Kaup, 1829) specimen (one of our collection of Ward’s Casts, like Shelley the Glyptodon) is under restoration after its long disappearance into storage, starting at the closing of the Wesleyan Natural History museum in Orange Judd Hall of Natural Sciences in 1957. The original from which our cast was made was found in the ‘Deinotherium sands’, of early late Miocene age (~9.5 million years old), in the neighborhood of the town of Eppelsheim (Germany). This original fossil is now in the collection of the Landes Museum in Darmstadt, Germany, and there is a Deinotherium museum in the town of Eppelsheim.

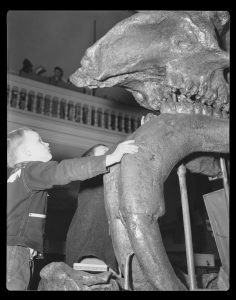

Our Deinotherium as it was in the museum in Judd Hall, with small visitor.

Photograph from Special Collections and Archives, Olin Library.

The large skull has been languishing in less-than-ideal storage conditions, first in the tunnels under Foss Hill, then in the penthouse of the Exley Science Center (after 1970). The Deinotherium was first catalogued as being present in two wooden crates in a remote corner of the penthouse in the summer of 2017, but only removed from storage and brought to the Machine Shop in the summer of 2018. Bruce Strickland in the Wesleyan Machine Shop has skillfully mounted it with customized hardware, and it is now balanced on a single pole. A new wood pedestal is being built.

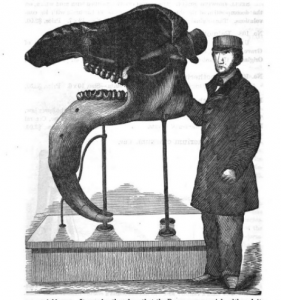

Ward’s catalog picture of the Deinotherium

The new mount of our Deinotherium on a single pole – before painting

In the catalogue of Ward Casts published in 1866 the Deinotherium skull was shown to be supported by three poles to support its immense weight. With the flair of the hardware engineers, however, it has been given a makeover – a modern sleek single-pole support.

The painting of the specimen begins with tedium, but modern technology makes our tasks easier. With many awkward nooks and crannies on and in the skull and teeth, painting with a paintbrush would be paramount to torture. We acquired gesso spray to coat the prepared specimen, allowing a prompt even priming of the surface for subsequent paint layers.

In the pursuit of faithfulness to the original specimen, we are restoring the cast in the color scheme of the original specimen from which our cast was made, from the Deinotheriumsande in Germany (and now in the museum in Darmstadt). The undercoat takes the form of a bright cream tone, upon which mottled splotches of darker colors were added to mimic variations on mineral content. A dilute grey-cream hue is then glazed over the specimen to better replicate the smooth bone-like texture, as well as adding interest and unity of tone. We work with a limited palette of six colors, and apply paint with natural sea-sponges in an effort to avoid brush strokes marring the authentic appearance of the cast.

The spectacular specimen will be displayed in the hallway by Woodhead Lounge in the Lobby of Exley by the end of the calendar year. In the meantime, we will keep you posted about our restoration process.

Photos courtesy of Andy Tan ’21.