Would you like to snorkel with giant predator reptiles the size of a small airplane?

Visit Level 3 of Exley Science Centre, where these spectacular beasts adorn our walls. And fear not, they are models, and the originals from which they are made have been petrified in stone for more than 100 million years.

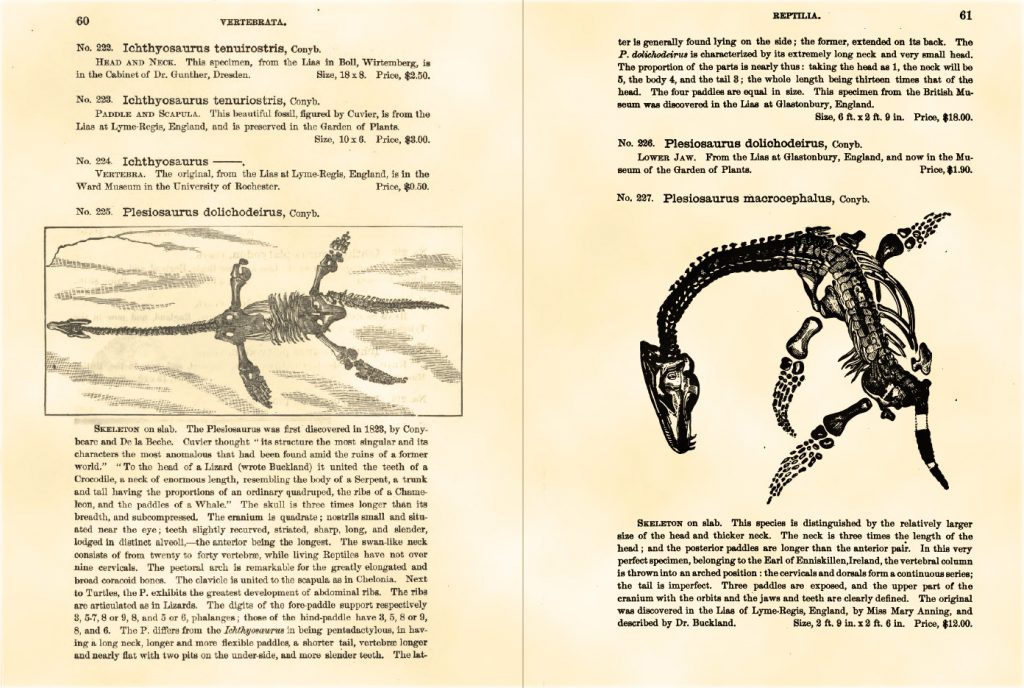

These fossil casts of animals which many children grew up knowing as Plesiosaurus and Ichthyosaurus have been plucked out of the obscurity of storage in the penthouse of Exley, where they had been collecting dust and mildew since 1957. Restoration efforts have brought these creatures back to their ferocious selves.

Once apex predators of the Mesozoic – the Age of the Dinosaurs – they have often been misrepresented as swimming dinosaurs. Ichthyosaurs were powerful swimmers that dived to great depths, their eyes protected from the high water pressure by bony shields. Plesiosaurs have such bizarrely long necks that their discoverer, a village girl named Mary Anning, was at some time accused by Georges Cuvier of fabricating a fossil by combining disparate body parts.

European scientists from colonial times are notorious for assuming the property of the conquered as theirs. Many of the world’s best fossils reside in institutions in Paris and London. In the 1800s, American professor Henry A. Ward decided that paleontologists in the US deserve to study the best fossils in the world without having to travel across the Atlantic, a long and expensive trip, and suffer bouts of seasickness. Apparently, rock folks weren’t that good with the choppy waters. He traveled to Europe and made copies of some of the most celebrated fossils of his time, and sold them to institutions in the United States.

The World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893 in Chicago showed a full series of these marvellously rendered casts, which were later showed as featured exhibits in the Field Museum. Wesleyan acquired a full series of these casts for its Natural History Museum in 1871 as a donation from Orange Judd. When the museum closed in 1957, they were crated and tossed unceremoniously into tunnels and penthouses around campus, where they remained for 60 years, until they were recently brought into the daylight once more.

Cover photo: Spinal processes of Rhomaleosaurus macrocephalus. Photo courtesy of Andy Tan’21.