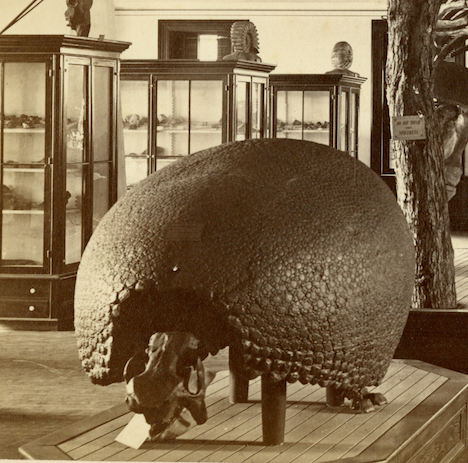

Our star Glyptodon is getting a new coat of paint after we stripped her of a large quantity of 60 year-old dust, with plenty of elbow grease. As with the other Ward Casts in our collection, she will be repainted with archival artist acrylic paints. The color of our Glyptodon is rather bleached from the harsh lighting during its days in the Wesleyan Museum (1871-1957). Archive photos from Special Collections and Archives at Olin Library at Wesleyan University, and photos of the same cast on public display in the Manitoba Museum show that she once sported a shinier and darker coat.

The sex of our Glyptodon cannot be determined from the material we have on hand. Hence according to a fairly recent tradition in assigning sex to these undetermined specimens in major museums and documentary productions, we are assuming that she was female when she lived. #davidattenborough

A chunk of missing plaster was taken out of the right side of the creature, at some time during its long storage. We filled the shallow hole with Plaster of Paris and hand-sanded it to match the contour of the dome carapace. With a traditional Chinese stone seal carving knife, we carved the scutes (bony plates or osteoderms) on the Glyptodon into the newly filled plaster. Some artistic license went into the reconstruction of the damaged part, which we adjusted to the surrounding area, as our research of Glyptodon scutes did not yield information pertinent to their restoration. However, each species of Glyptodon had its own unique pattern of scutes.

To match the color of the original cast, we performed a spot test on and around the plaster fill. This spot was chosen in part because we were excited and a tad anxious to see how the restoration would turn out. Using an old worn-out brush with stiff bristles to stipple various shades of browns and darks over an undercoat of yellow ochre, we painted in the plaster restoration. It turned out rather satisfactory, with the color not distinguishable from the surrounding areas.

Many more tubs of paint away from completion, the results are looking encouraging. In the mean time, we are also working on restoring a cast of the holoytype of Mosasaurus hoffmanni, a source of political drama and contention between European governments. But more about that next time. – or see here for a first start of the saga of the mosasaur Our cast of this fossil was in a tremendously lamentable state when we found it in the penthouse of Exley. #déjàvu

Large pieces of plaster were missing, including a broken tooth and a missing piece from the broken mandible the size of a tortilla chip. We have since sculpted the missing parts in plaster, which happens to be a notoriously challenging medium to work in. Once prepared, the plaster is workable for only 15 minutes before it cures, and it has a creamy consistency akin to that of mashed potatoes. Once the plaster cures, it is slowly hand-sanded to shape and painted with a matching colour mix.

The careful reconstruction of these fossil casts play a significant part in reconstructing the history of paleontology. When fossil hunting was a trending field of study in Europe in the late 1800s, fossil specimens were found all over Europe in large numbers, with paleontologists in the US catching up in the late 1800s, specifically with the construction of railroads into the US west. In the 1860s, a visionary in the field, Henry A. Ward, an American geologist and naturalist and professor at Rochester University (and the founder of the present Ward’s Science company) , felt that the US public missed out on the opportunity to see the most famous fossils, and made an effort to provide access for scholars in the US to important fossil material: in 1866 he published his Catalogue of Casts of Fossils from the Principal Museums of Europe and America. His ambition and foresight laid the foundation for a generation of American paleontological work and public awareness on evolutionary theory based on these materials. Orange Judd provided funding to buy the complete series of casts when the Orange Judd Hall was finished in 1871, including the Giant Ground Sloth, Megatherium cuvieri, and Plesiosaurus cramptoni, 22 ft long; sadly, these two giant casts have been lost at the dissolution of the Wesleyan Museum.

Cover photo: Glyptodon carapace detail prior to repainting from the Joe Webb Peoples Museum collection at Wesleyan University. Photo courtesy of Andy Tan ’21.