In this special edition of Unseen Wesleyan, we interviewed Mr. Paul Hadzima ’59, the last student curator of the Orange Judd Museum of Natural History. He worked at the museum in 1957, the year when the Judd Museum ceased to exist. After receiving a Bachelor of Arts in Geology, and a MAT with a concentration in history, he went on to teach earth science and history in the high school at Woodbury, Connecticut for 36 years, before retiring. Here is our interview with Mr. Paul Hadzima.

Melissa M.: How did you get involved with the Orange Judd Museum of Natural History?

Paul H.: Since the Geology Department was responsible for the museum, it was normal for a geology student – a sophomore or a junior – to help out with the museum. I was there at the time as a sophomore geology major student, and there was not any other applicant, which was why I took up the job

Melissa M.: Was it just only one student working in the museum at that time?

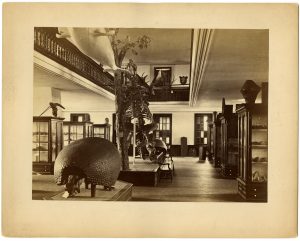

Paul H.: Yes, actually. At that point, the museum had really faded, and the interest was not there anymore. In truth, it was not very clear why we had the natural history museum by that time. At the founding of the Orange Judd Museum, it was believed that natural history was a subject that everybody should know about; so, you want to have every aspect of natural history in it. By the end of the 19th century, you wanted to develop a specialized field like Geology or Physics where one has razor-like focus on that particular field. The museum’s place in the University [as it was quite an all-encompassing natural history museum] became vague and difficult to define.

Melissa M.: How long did you work in the museum?

Paul H.: I worked in the museum for a year. I had hoped I could have worked in the museum for longer than that, but the museum disappeared from under my feet – so to speak. So, I worked in the museum for a little more than a year altogether.

Bright P.: So, what was the museum like? What was your favorite specimen in the museum?

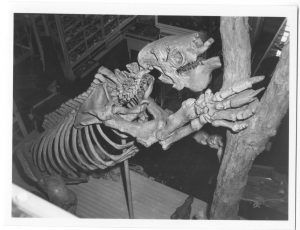

Paul H.: As I mentioned before, I was attracted to some of the Native American artifacts in the museum. I was impressed with the Glyptodon and Megatherium – the giant armadillo and the giant sloth – mainly because it gave me the imagination of how large the fauna was in North America during the fairly recent period. The fact that a sloth could be that big, from something a foot long to eight feet across; it was no wonder that Mammoth and Mastodon could have been that big. As I said, as far as fossil was concerned, I liked the fossil fish mainly because it was such an unlikely animal to be fossilized.

Paul H.: You see the size of the carapace of the shell?

Both: Yea

Paul H.: It was enormous, and you had the tail coming out at the back; and unlike the armadillo, its shell was like a turtle. And it had its head coming out – maybe you gotta look for the head now.

Both: Oh yea! [Chuckle]

Paul H.: I believed there was a foot coming out. It was like maybe six to eight feet across? After sixty years it was pretty hard to remember things now. You should look into the photo from the time, so you know what other pieces to look for. So, where are you thinking of putting the replica now? Maybe you could set it up in the lobby with the fossil foot prints?

Melissa M.: Oh yea maybe, Professor Ellen was talking about that and I said “what if some drunk student start climbing up on it?” [Chuckle]

Paul H.: That’s true, maybe you should build a fence around it or something? [Chuckle] It was very impressive. The stuffed animals were nice, but you know, they are mostly gone.

Melissa M.: We still have some I think, they were rescued I guess. We found some peacocks and a pelican in the storage room.

Paul H.: What is your buffalo called?

Melissa M.: I think his name is Greg.

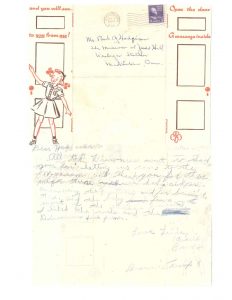

Paul H.: There was a wolf I believed; and as the young lady said in the Thank You note, there was a fawn and maybe a mother to go with it.

Bright P.: I think the wolf went to the Smithsonian, according to the record.

Paul H.: Ah, maybe.

Melissa M.: Can you describe your typical work day at the museum?

Paul H.: Most of the time, I would be there for two days a week; usually I would in the afternoon and stay through dinner time. Normally, we had a sprinkling of people come. But in almost every week, we had a Boy Scout group and a Brownie group, some younger people.

Thank-you note to Mr. Hadzima from Middletown Brownie group.

And in many ways, the museum was of greatest interest to them. Although some collections, predictably the minerals and the fossils, were such that students of that would be interested and would come up. Most of the other things – and I believed this was the idea of it – were a natural history extravaganza, to get the kids to maybe get an interest in science.

Bright P.: Was there any active research or cataloging of the museum’s specimens while you were working in the museum?

Paul H.: Not at all. I think, by that time, people saw the end coming. The idea of eliminating the museum went back quite a way. People were always saying “Why do we have this, why do we have this?” The museum either had to get bigger to make it more significant, or we had to get rid of it. And some of the articles [in the news at the time] said that the Psychology Department needed space. They were becoming more than a class room type of discipline. They wanted room for their lab rats. They expanded quite a bit in the post-World War 2 period. They had basically one floor, maybe a floor and a half. At that point, Judd Hall – in the basement floor – was a Music Department.

Melissa M.: Oh, so the Judd Hall was just the museum and the Music Department in the basement? Or was there also a Psychology Department in there?

Paul H.: There was at that point: Music in the basement, Psychology on the first floor, Geology on the second and third floor, and the museum above that. So, there was an awful lot in there. And no major changes were made to the sciences until Exley, which was built in the 70s I believe. So, you had, and this was in 1957, around 15 years when nothing was proposed and nothing was built. So, poor museum had to go, I think. When all of these science disciplines needed space, there was not enough space for the museum. So, when they reopened, the Music Department was gone and the Psychology Department had the first and second floors, and the Geology Department had the third and fourth floors.

Melissa M.: You talked about this earlier, but you were not involved in packing up the museum?

Paul H.: No. I did a little of the prep-work; then I know that they needed this to be done right away, so I had another job during the summer. Even though I thought I saw myself in one of the pictures, I was not involved with packing up.

Melissa M.: An imposter! [Chuckle]

Paul H.: [Laugh] I don’t think I was there.

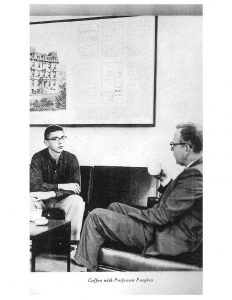

Mr. Hadzima and Prof. Joe Webb Peoples, after whom our museum is named.

Bright P.: How has your work experience at the museum influenced your career afterward?

Paul H.: Well, in some interesting ways, I think the thing I had decided by that point, by the end of the sophomore year, was that I would not become a geologist in the sense of a researcher, hunting for oil in the plains of South Texas. One of the thing I enjoyed doing, I found out, was instructing the groups that came in. And what this did, was to lead me to become a teacher. Also, the idea of teaching earth science in a broader sense, because in high school, at that point, was about geology, the weather, and paleontology. Unlike what I would have ended up in if I had become a researcher, where you would do something in a very specific area of geology. This instruction experience appealed to me quite a bit. And then also, I probably recognized at that point, the Native American stuff began my interest in anthropology, which continues to this day.

Melissa M.: Did you have any interesting story from the museum?

Paul H.: I tried to think of the specifics, but after sixty years, all the little ones tended to disappear. It tended to be a fairly quiet thing. We did not have people doing wild stuff and stealing the mummy or anything else at that point. Most of the crazy things that happened came after the mummy was unwrapped. And, I guessed they did not find much when they unwrapped it, is that correct?

Melissa M.: Jessie [Ms. Jessie Cohen, Archaeological Collections Manager and Repatriation Coordinator, Archaeology and Anthropology collections, 3d Floor, Exley] told us that they did an x-ray at the Middlesex hospital. They found out that he was a man in his twenties who was probably of high status because he did not have wear-and-tear in his hands. [Note: the X-rays were made in 1978, and are available in the special collections at Olin Library]

Paul H.: And by the fact that he had a coffin and he was fully mummified, which was an expensive proposition. But most of that happened after my time. So, I can’t really come up with any stories, although I can make up some stories, but I don’t think that’s what you are looking for.

Both: [Chuckle]

Paul H.: The experience itself was, to me, very worthwhile. I did not get paid very much. You said you got the book that said how much each was paid?

Melissa M.: Oh yes, I believe Ellen [Professor Ellen Thomas, Faculty Mentor on the Joe Webb Peoples Museum Project] has that. [Note: these records have been moved to the Special Collections at Olin Library earlier this year].

Paul H.: I would like to see that sometimes. See what the pay was. Working with the department, and professor Joe Webb Peoples himself, because he was much of a people’s person himself; he did great things.

Melissa M: I guess you have to be that if you have that last name.

Paul H.: I guess you had to; I think he had some southern roots and all. He was responsible for a lot of important stuffs [for the people and Wesleyan University], including the establishment of the Dinosaur State Park. I believe he had a lot of contacts in the state legislature; so, that made it very much worthwhile, even though it was a dollar per hour or however much it was.

Bright P.: What advice would you give to colleges and universities working to maintain and display their museum collections?

Paul H.: The first thing I would advise them is to stop and think “Why do we do this?” I mean, granted, at this point, you have a wonderful collection of materiel; and it is really great that you are moving ahead with having it be more available to the public to see. But, in a way, unless you have a very sizeable collection to start with, to put together a museum is almost impossible. What people did a hundred year ago on these expeditions and came back with all kind of stuff, this can’t happen anymore. You can’t go into the Native American cultural area anymore and have this happen. You are not going to find, Ellen was talking about the other day, an area where they are putting road to and come back with several enormous fossils of the Pleistocene period. It’s just not gonna happen. There must be a reason for [establishing a museum] if you are trying to bring people into your school and advertise what you have. But, with the number of museum around right now, I don’t think I advise anybody to start one. But, maybe if you have a collection and you cannot be bothered to do a decent job on it, maybe it is best to give it away; I don’t know. What do you think?

Melissa M.: I feel like it is important to have a lot of people exposed to the material you have. Even if you don’t make a museum, maybe display cases for class would be useful.

Melissa M.: Yea, It could help, especially school groups. I think if I was a school student I would love that.

Paul H.: I suppose you could say, in a way, it was too bad in 1957 that this had to happen. That somebody couldn’t have found a rich donor who could have given the money to have a modern building or section of a modern building put up. And for the collection, you couldn’t have brought in a curator, because we didn’t have a professional curator for the last years of the museum, to go through the collections. So that they could find some attributions, because some of these things are lacking in details. Like red stone from South Dakota

Melissa M.: Or some unidentified mammal.

Paul H.: And that was the point, if someone was willing to spend some money. You could have probably done something or got some grant and so forth. But I didn’t think there was any real interest at that point doing that.

Melissa M.: I guess because of the lack of resources.

Paul H.: Right right. I don’t know if you are familiar with what was going on with the educational philosophy, and the battle that was going on at that time. The president, who was a guy name Victor Butterfield [Note: Wesleyan’s 11th president, 1943-1967], who was an advocate for a liberal art education for everyone, fought against the various departments who wanted to really emphasize the great knowledge of their particular field, and the people who wanted to do that. And you had this big tug-of-war between the two. Basically, the museum probably fell between the tension of the two groups because it didn’t fit with either one [vision]. Well, I guess Butterfield would have liked it, but he didn’t have the money needed to do things that further liberalize the education. It was an interesting time period.

Melissa M.: Thank you so much for answering our questions.

Paul H.: I enjoyed it a whole lot. Obviously, with my interest in history and genealogy, I enjoy seeing the part of the university which is still here from the time that I was here. It was very surreal to walk around the campus in 2017 when I was here in 1957, and seeing something that still look the same.

Melissa M.: Does the bison still look the same?

Paul H.: The bison looked better actually [chuckle]

Melissa M.: It had a spa treatment recently [audible laugh]

Paul H.: [Seeing] the buildings that look the same, and the buildings which, you know, the complex that nobody really thought of at the time. We had everybody essentially living in three dorms.

Melissa M.: Which three dorms?

Paul H.: Clark Hall, North College, which was a dorm at the time, and Harriman Hall, which was above the PAC – the Public Affair Center – that was a dorm. Everybody was living in either these three dorms or in a fraternity house, and there were thirteen fraternity houses. And everybody wanted to live in a fraternity immediately, because there was not enough room for everybody to be living in college facility. And everybody ate in fraternity houses, there was no college general eating place like Usdan [The Usdan University Center at Wesleyan University].

By Sajirat Palakarn

By Sajirat Palakarn