Egg-collecting was a mania in Victorian England, and collectors such as Lord Rothschild collected 11,750 egg-sets in his curiosity collection. Naturally, collectors in America followed suit, and egg shells became a staple in museum cabinets. The former Wesleyan Museum in Judd Hall housed a large bird egg collection, most of which were deaccessioned and sent to the Smithsonian Institution when the museum was closed in 1957. Most, but not all.

Since 2017, the Museum has been upgrading its storage methods to a more controlled, secure and space-efficient system for the first time in over 60 years. Many of our deteriorating drawers and teetering cabinets are being decommissioned, with more specimens fitted into the modern storage cabinets. Within one of these decaying storage cabinets that mostly contained mollusks, we discovered a tray of dust-laden bird eggs, some broken, some loosely boxed, some buried in old newspapers and sawdust.

One of the specimens was unfortunately shattered into many pieces. Given that this was an irreplaceable specimen collected over a hundred years ago, we did our utmost to preserve and conserve it. We took care to slowly match the delicate pieces together, and repaired the specimen with Paraloid B-72 resin. It was slow, tedious work. Eyes start watering about an hour into the job, but four hours later, the entire egg was back into one piece again. If only Humpty Dumpty had been sent to us.

The cleaning process was not easier than the repair-job: we used museum grade applicators a.k.a. Q-tips to carefully treat the delicate egg shells to remove the thick layer of grime and dust collected in over 60 years. Care was taken to not over-saturate the shells with the cleaning solution of mild detergent, so as not to weaken it. After cleaning, the egg shells were lovingly cradled within appropriately-sized archival museum boxes. We also stored the old newspapers and sawdust in sealed jars for their historical interest and value.

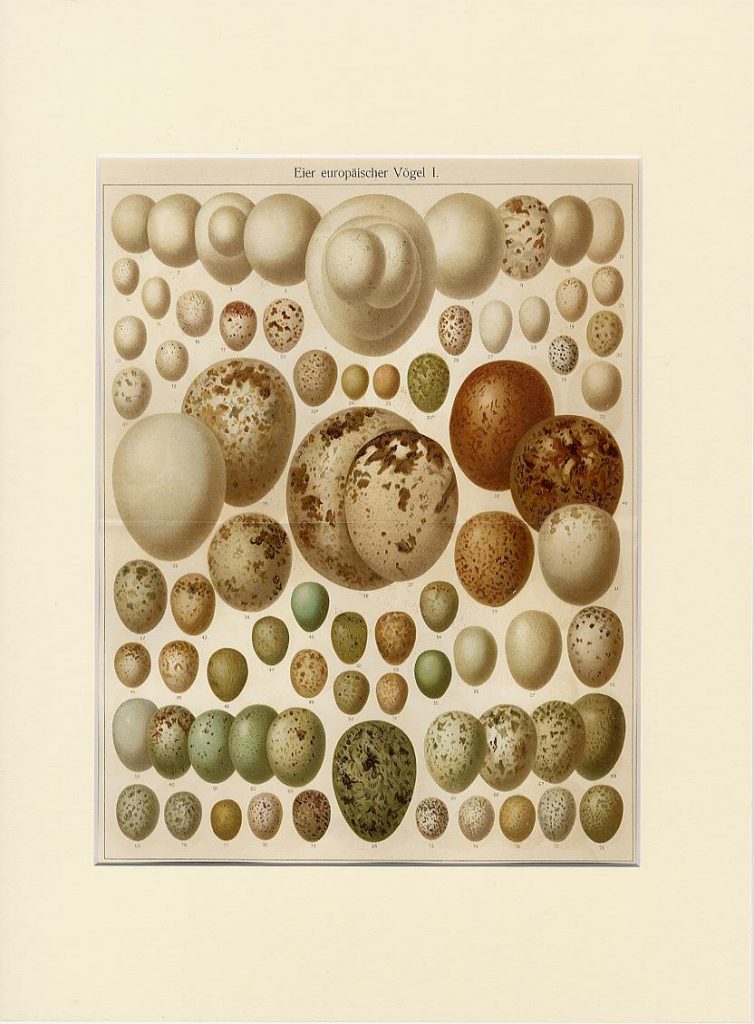

An important part of the value of collections is their history and potential to contribute to scientific knowledge. Data including – but not limited to- locality and time of collection help researchers determine ecologically significant changes in populations, and/or reassign taxonomic affiliations. The bird eggs were found mostly without labels, but we hope to reconcile them with their accession records by matching the catalogue numbers etched onto them with our record books. Any natural history specimen without a label is still a pretty curiosity upon which to gaze.

We traced a significant portion of the specimens to the collection of Charles H. Neff, a local (Portland CT) collector active in the late 1800s and earliest 1900s. He was a person of diverse interests, as reflected in his collections of taxidermy birds, eggs, minerals and anthropological specimens. The Special Collections and Archives in Olin Library holds a volume of his field notes, in which Neff, in fine penmanship, detailed his bird-watching field trips, often including local weather observations. Notes such as these may provide crucial information for researchers hoping to trace the distribution of species and migration patterns over time, and potential effects of climate change on species distributions. He donated a vast number of specimens to Wesleyan, alongside carefully curated labels and accession records.

A common question is: how were such fragile objects preserved? The answer is rather straightforward. The eggs were typically taken directly from the nest, to the great dismay of the parent birds. They were then drilled or cut open, shaken to break up the yolk, and emptied. The insides then were washed and dried. Some preparations called for the consolidation of these fragile pieces by coating the insides with glue or some other consolidant. You can make a weekend project out of this using chicken eggs. Steer clear of wild clutches of eggs, since wild species should be left in peace and you may run afoul of local legislation.