Fossilisation is nature’s way of preserving traces of once living organisms, humans too have devised ways to intervene with decomposition and to preserve life in a more predictable and accessible manner. We are a species of control freaks.

The business of science in the 1800s was to collect and classify all known life on the planet. Our museum collections house two collections of preserved specimens, one of birds and one of “wet” specimens. Both of these collections were amassed in the late 1800s for teaching purposes in the observational taxonomic sciences. They became increasingly neglected after the frenzy for laboratory sciences began to grow in the 1890s. In a dusty and creepy Shanklin store room chock full of gloom and antique cabinetry, we stumbled upon shelves of some 300 alcohol-filled glass jars with various curious-looking animals and plants. Hiding places at Wesleyan are simply inexhaustible.

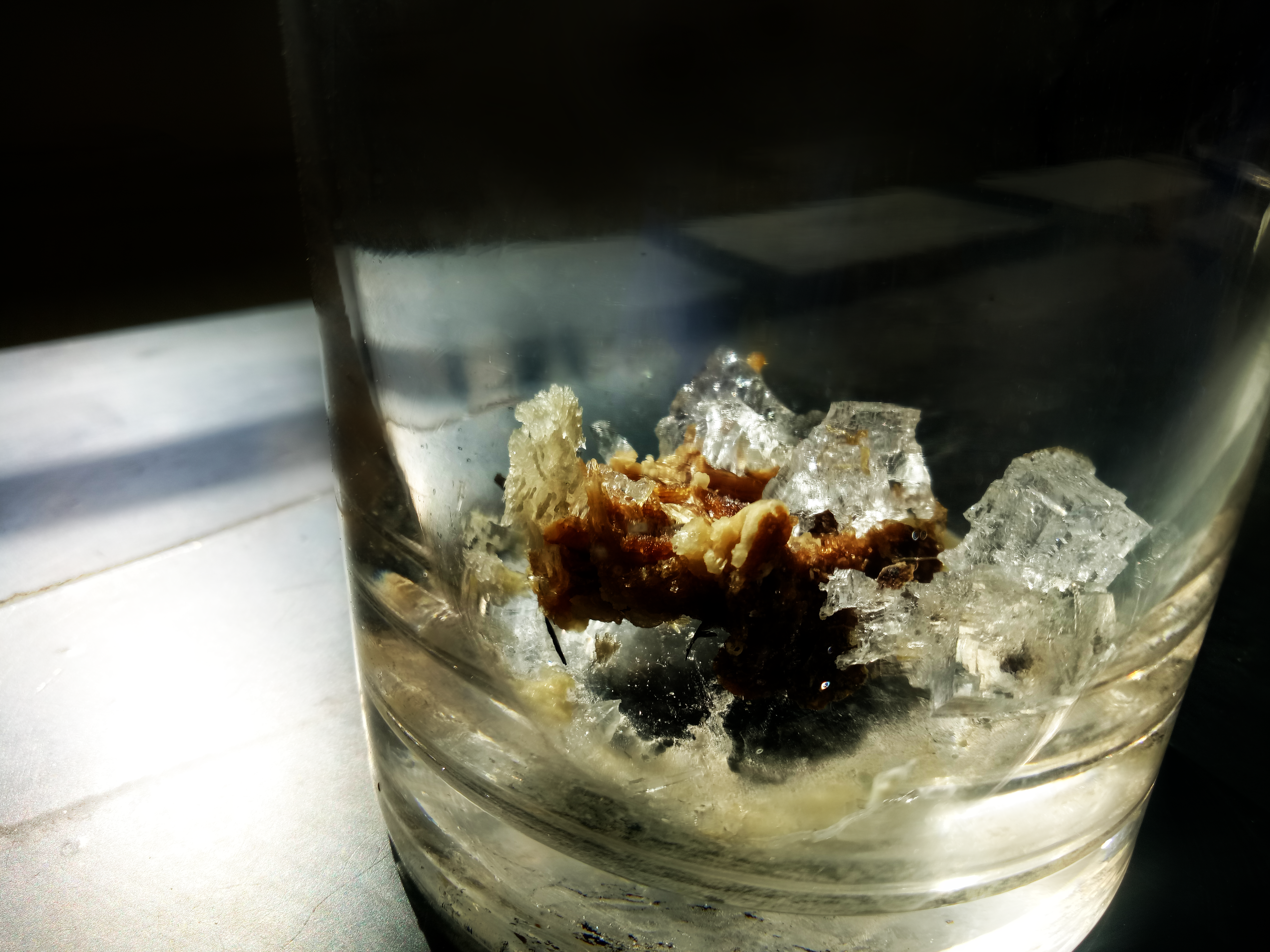

Working with the “wet” specimens from the 1800s is a wild ride. Many jars that came out of storage were dried out from a compromised seal. Many delicate specimens like that of jellyfish have disintegrated beyond recognition. There is, however, beauty even in the face of destruction. In several desiccated jars of marine specimens, the slow evaporation of alcohol has precipitated glistening crystals of salt that I would be proud to wear around my neck. Unfortunately, they would dissolve in the rain.

Back in the 1800s, travelling was difficult and severely limited. Most people would not have travelled to the neighbouring state, much less Africa, Nova Scotia or other far-flung locations. Missionaries and scientists travelling the world assumed the responsibility to bring back natural curiosities from their destinations. Fixed and stored in ethanol or foul formalin, the animals and plants are morphologically preserved for hundreds of years. These specimens were the sole source of visual information for students in the life sciences before the days of Powerpoint and Moodle.

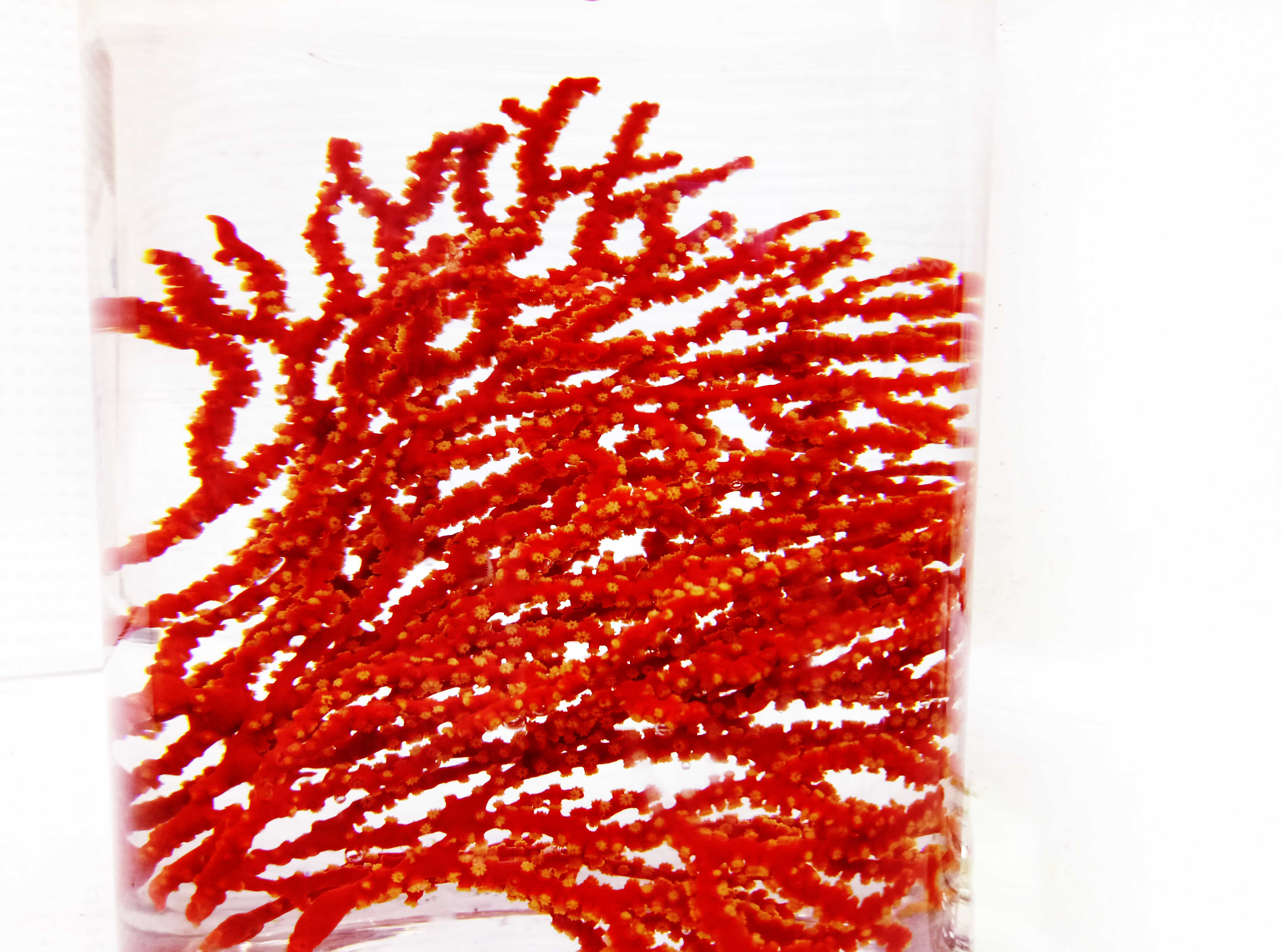

Unsurprisingly, elusive marine organisms became a focus of the collection. Yet it seems a little bizarre that the most well-represented group of animals in our animal pickle collection are polychaete worms. These critters from the highly diverse group of animals called annelids – the segmented worms – are common yet elusive in many marine habitats today.

One of the stars of our collection is literally a star. Ambiguous as to whether it is a beast or plant, our mesmerising basket star belongs to a group related to the brittle stars. It’s flamboyant branched arms were used to capture planktons and other food particles adrift in the currents. Living up to its name, the specimen was incredibly brittle and required extreme care when we transferred it into a new jar with fresh preserving fluids. It is now steeping in alcohol to reverse over 100 years of dehydration. Even with its many merits, our basket star is only one of the many alien-like wonders in the sealed jars. Our collections comprises of 21 Phyla of animals listed below. A phylum is a large group of animals sharing a similar body plan.

i. Porifera: Sponges

ii. Ctenophora: Comb Jellies

iii. Cnidaria: Jellyfish, corals and allies

iv. Echinodermata: Seastars, sea urchins, sea lilies, sea cucumbers and allies

v. Mollusca: Clams, snails, cuttlefish and allies

vi. Brachiopoda: Lamp shells

vii. Bryozoa: A group of marine filter feeders

viii. Annelida: Ringed worms

ix. Sipuncula: Sipuncle worms

x. Nermatea: Ribbon worms

xi. Nematoda: Roundworms

xii. Chordata: Animals with a notochord, including all vertebrates

xiii. Hemichordata: A group of worm-like marine animals related to the echinoderms

xiv. Arthropoda: Segmented animals including insects, crustaceans and spiders

xv. Angiosperma: Flowering seed-bearing plants

xvi. Chlorophyta. Green algae

xvii. Coniferophyta: Pines and allies

xviii. Pteridophyta: Ferns and tree ferns

xix. Charophyta: Red and brown algae

xx. Hepatophyta: Liverworts

xxi. Bryophyta: Mosses

We will be exhibiting many of these relics that illuminate the history of Sciences at Wesleyan around campus. Keep your eyes peeled for temporary installations of these spectacles from the 1800s in the Fall semester!!

Cover photo: Gills of Squilla sp. preserved in 70% ethanol.