The history of life is a long story to tell, reaching over billions of years, while the history of shelving it is a far more manageable one, reaching over centennia.

This exhibition is curated to explore both of these rich histories – the history of life and the history of people trying to ‘arrange life’, i.e., shelving it, putting it into cabinets and museums and onto shelves. We are featuring collections of the natural world as assembled in the mid to late 1800s in a reconstructed 19th century ‘cabinet of curiosities’, as well as in the context of modern understanding of science.

Museums started in the homes of rich and powerful men in western Europe as ‘cabinets of curiosities’, various beautiful or weird objects. Many objects in these gentrified cabinets were not or not fully identified, hence curiosities, which include objects that we now call rocks, minerals, fossils, taxidermy specimens of animals, shells, corals, bones, eggs, animal and plant specimens preserved in alcohol, pressed plants, archaeological and ethnological objects including coins, cameos, and objects of art.

Wesleyan’s former museum in the Judd Hall of Natural Sciences housed a large number of these spectacular displays that speaks of a glamorous, but in part somewhat unfortunate past. The extensive and delightful collections were made mainly for the instruction or entertainment of the elites. The cabinets commonly had no labels to explain their contents, so that many would have found the objects intriguing but inaccessible. Specimens were obtained by killing animals – breaking coral heads from a reef, or killing birds and butterflies, without much thought for the natural ecosystems. Archaeological and ethnological objects were taken, in many cases without consent of their owners. And scientifically, in many cases, there is insufficient information given on the location where specimens were collected to have their full value for present-day scientists.

Under the influence of the first director of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, George Brown Goode, Wesleyan Museum’s first curator, who was pivotal in framing the modern, three-legged purpose of a natural history museum (preservation, research, education), we are repurposing these collections in the fashion of modern museums – with labels written to inspire learning. We are featuring three thematic displays of evolution of novel forms: elephants, fish, and flight.

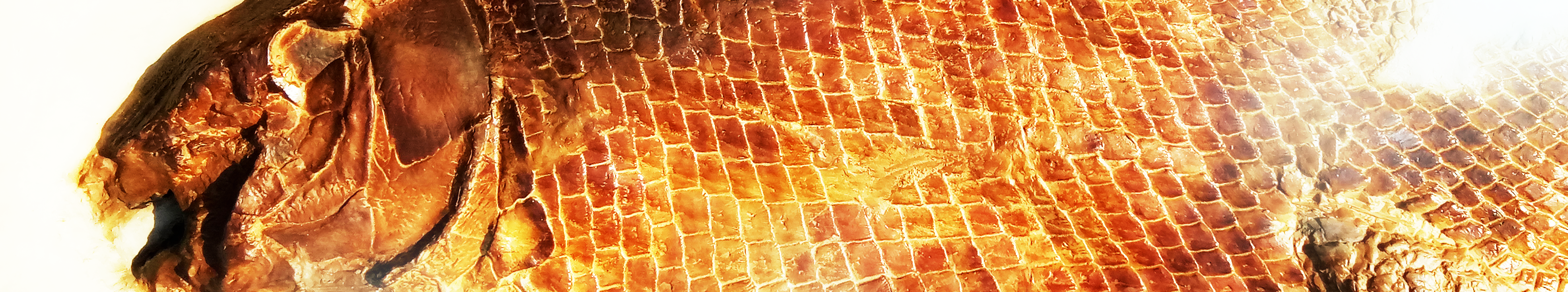

Elephants and their extinct relatives demonstrate how morphology gives us clues about function and evolutionary relationships; extinct and modern fishes illustrate forms such as ganoid scales, that persist through long periods of evolution; flying vertebrates show how birds are dinosaurs.

The exhibition will be on display throughout the 15th of October. The opening reception will be held on the 28th of September from 4 -6 pm, with refreshments served.

Scan the code below or follow this link to explore curiosities at Wesleyan.

We hope that whatever you see, you will never forget.

Cover Photo: Scheenstia maximus, Late Jurassic fish, Ward’s cast. This 6-feet-long specimen is one of the few surviving Ward Cast replicas of this species . It is an important specimen in the collection, as the original specimen has been destroyed in World War II. Photo courtesy of Andy Tan’21.