Science was not like it is today in the 18th and even 19th century: things people used to do in science at that time – not too long ago -may appear very odd to us. In Wesleyan’s collections lie several keystone artifacts to this rather fascinating episode in history. Before science (as we consider it now) existed, people thought that living species of animals had always existed and will always exist – the idea that there was such a thing as ‘extinction’ was not realized. It was not until the 1830s that one of the most important figures in the history of paleontology played a role in awakening the world of science to the actuality of extinction. She was Mary Anning, the daughter of an English cabinet maker, who discovered groundbreaking specimens pivotal to this paradigm shift, but she was not given credit for her important contributions during her life time.

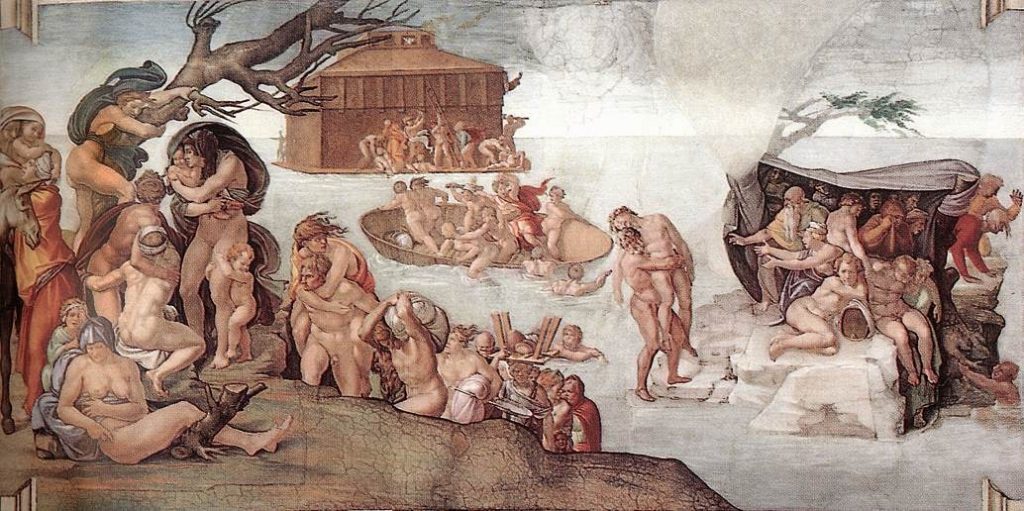

Even when the celebrated star in paleontology, Georges Cuvier, published a first authoritative paper on extinctions in 1879, the general public did not take it lightly that Divine Providence was doubted by the idea of extinction of creatures, which had been designed and made by that Providence. Even when described by a man who mesmerized the European public with the fascinating animals he put together from a box of disarticulated bones, the community did not warm up to the concept of extinction. Why would God create animals only to wipe them out later? This idea was contrary to the prevalent notion that everything created has its permanent, perfectly designated place and purpose in the world, fitting into the Great Chain of Being.

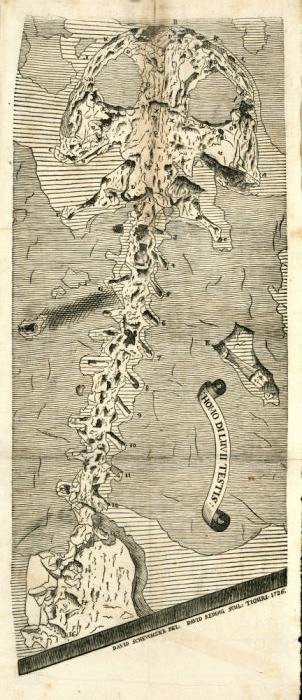

The Oeningen Formation in Germany contains a vast trove of beautifully preserved fossils, including some spectacular plant leaves, with leaf veins visible, and what have been called ‘perhaps the richest insect deposits in Europe’, dating back to the late Miocene (~6-11.5 million years). In the 1700s, long before the research by Mary Anning or Georges Cuvier, an odd fossil was dug up from these sediments. The identity of the remains was an enigma. To the contemporary scholars, this could only be the remains of something that still existed on Earth, because the concept of extinction had not yet been worked out. Swiss scholar – scientist was not a job title back then – Johann Jakob Scheuchzer gave the scholarly community the most obvious answer to this conundrum in 1726, illustrating the tension between science and religion. This must have been “The Man Who Witnessed the Biblical Flood”, in Latin ‘Homo diluvii testis’.

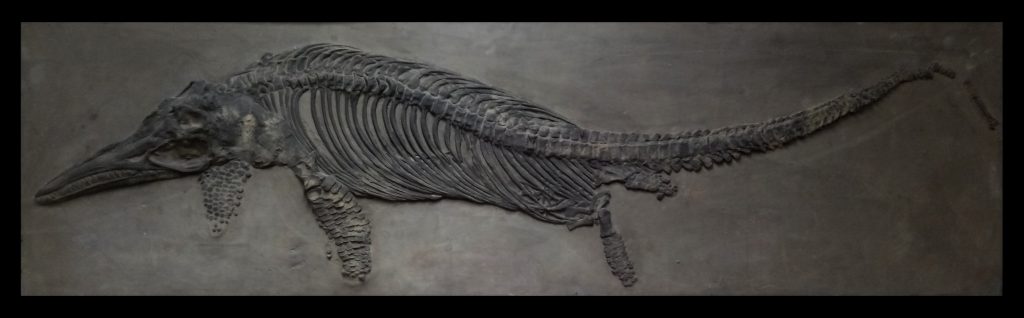

Other naturalists expressed doubts on the human origins. Johannes Gessner (1758) though it was a catfish, the Dutch naturalist Petrus Camper (1777) thought it was a lizard – at that time, the distinction between amphibians and reptiles had not been made. Georges Cuvier looked at the fossil in 1811 (at which time it was on display at Teyler’s Museum in the Netherlands -where it still is). He removed sediment covering part of it so he could see a larger part of its skeleton, including its front legs. This was a man who boasted he could reconstruct an animal from a single tooth, and he quickly determined that the fossil was that of a giant salamander which no longer lived on Earth. The fossil was named Salamander scheuchzeri by Friedrich Holl (1831), then given a new generic name, Andrias, in 1837 (by Johann Jakob von Tschudi). Perhaps taking a jive at Scheuchzer’s ideas, the new name, Andrias scheuchzeri, meant “image of man of Scheuzer”. The Joe Webb Peoples Museum on Level 4 of Exley houses a cast of this giant salamander, measuring about 3 feet in length.

Science has come a very long way in a very short period of time, but people are still catching up. Science ‘as we know it’ has had a place within the last 10% of the ~ 5000 years of recorded history only. It has only been 300 years since we first looked at the Moon and decided that there are no people living on it. It has only been less than 100 years since the advent of modern medicine. 50 years since the first moon landing. 15 since the first human genome sequenced. Today, we still sometime struggle with beliefs that fossils are the work of the Devil.

Living in a time when the authority of science as a source of empirical truth (or even the existence of such a thing as ’empirical truth’) is undermined by political and religious leaders, the increased understanding provided by scientific pursuit is under daily threat.

Come to the Joe Webb Peoples Museum of Natural History on Level 4 of Exley, and feast your eyes on our fossils with a beauty superseding any text written in stone.

We stand on the shoulders of Giants…

Cover photo: Andrias scheuzeri spine details from the Wesleyan Joe Webb Peoples Museum natural history collection. Photo courtesy of Andy Tan ’21.