A crinoid fossil from Crawfordsville, Indiana in the Wesleyan University Joe Webb Peoples Museum (4th Floor Exley Science Center).

Crinoids are organisms that are neither abundant nor familiar to most people in today’s oceans. However, during most of the Paleozoic Era (from the Ordovician on) and in the early Mesozoic (Late Triassic through Jurassic), crinoids flourished in marine environments, carpeting the seafloor like a dense meadow of flowers. It is estimated that the number of extinct species of crinoids in the Paleozoic was 5 to 10 times greater than the 600 to 800 species that are currently living.[1]

Because of their “flower like” appearance, crinoids have been referred to as “sea lilies”, but do not be fooled: they are in fact animals. Crinoids belong to the phylum Echinodermata. Like other Echinoderms—sea stars, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers—crinoids have rough surfaces, five-sided symmetry, a calcium carbonate endoskeleton, a nervous system network without a central brain, and the ability to regenerate damaged body parts.[2]

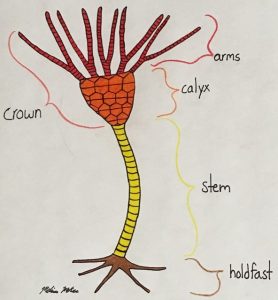

In general, crinoids have four main body parts. The first are food-gathering arms. The arms have tiny ‘hairs’ (tube-feet, part of a hollow, hydraulic system present in all echinoderms) that capture suspended food particles and direct them towards the mouth. The number of arms varies from five, common in primitive species, to as many as 200 in some living species, but the number of arms is always a multiple of five.[3] The arms project from the second main body part, the calyx, which encompasses the crinoid’s major soft-bodied tissues and organs.[4] The lower part of the calyx is made up of rigid, five-sided plates.[5] The calyx and the associated arms are collectively referred to as the crown. Next is the stem, which is composed of a series of flat discs that pile on one another like a stack of coins (with a hole in the center). These stem pieces come in a variety of shapes—round, pentagonal, star-shaped, or elliptical. The stem elevates the crinoid’s body into a more sediment free zone above the sea floor.[6] Lastly, the holdfast anchors the crinoid’s stem to the sea floor. The now-extinct crinoids of the Paleozoic were predominantly fixed by their stalk to the ocean floor, although some crinoids lived attached to driftwood floating in surface waters, but only about ten percent of crinoids living today are estimated to have stems.[7] Non stalked forms are called comatulids (or feather stars).

The parts of a typical crinoid with a stem from the Paleozoic. Illustration by Melissa McKee.

Wesleyan University’s Joe Webb Peoples Museum has an amazing collection of crinoids from Crawfordsville, Indiana, which were donated by Henry I. Nettleton, in the late 1800s. The crinoids from localities in and near Crawfordsville are world renowned for their amazing diversity, abundance, large size, preservation, and superb three-dimensional relief. In addition, the beautiful blue-gray colors of these fossils appeal widely to both fossil collectors and museum visitors.[8]

More examples of the crinoid fossils from Crawfordsville, in the Joe Webb Peoples Museum of Wesleyan University.

The preservation of the crinoids from Crawfordsville is very unusual. Crinoids are made up of multiple calcium carbonate plates held together by soft tissues, primarily ligaments. The ligaments are readily biodegradable. As a result, when crinoids die, their ligaments typically decompose within hours or a few days, leaving their plates to be easily scattered by currents or predators. Consequently, crinoid fossils are almost always found as what has become known as “crinoid hash”—scattered crinoid pieces. However, the Crawfordsville area had both shallow water conditions and an influx of silt from a neighboring delta. This caused the crinoids to be periodically buried alive by storm-generated slumping or silt flows. The crinoids were buried deep enough to avoid decomposition and predation, allowing for remarkable preservation.[9]

A sample of crinoid hash. Crinoid stem fragments are visible.

The Crawfordsville locality offers unprecedented insight into the ecology, morphology, and behavior of Mississippian-age (~ 350 million years) crinoid communities. Nearly half of the species found at Crawfordsville have at least one complete specimen, making it possible to determine the height of that species when it was alive. This helped scientists answer the question of how so many diverse crinoid species could thrive in such close proximity.[10] A clue is that different crinoid species are found with differing stem lengths, allowing each to find its own feeding niche in the water column. Additionally, even crinoids with stems of similar length can filter food particles of different sizes, as shown by different structure of their ‘arms’. In these ways, competition between the species was minimized and diversity could be maintained. This ecological phenomenon has become known as tiering, and is now widely recognized to have been an important aspect of the structure of benthic marine communities throughout much of the Phanerozoic[11], with tiering of suspension feeders most common in Silurian through Carboniferous and Late Triassic through Jurassic.[12] In today’s oceans, such highly diverse tiers of epifaunal organisms are no longer present, with too many active predators (fish, sea urchin) feeding in the water column.

By Melissa McKee

[1] Moore, R.C. and C. Teichert, eds, 1978. Introduction. In: Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part T, Echinodermata 2, Vol. 1, T7-T9. R.C. Moore and C. Teichert, eds. Geological Society of America and University of Kansas. [2] Morgan, W. W., 2014, Collector’s Guide to Crawfordsville Crinoids, Schiffer Publishing, Limited. [3] Brosius, L., 2005, Fossil Crinoids: Kansas Geological Society. [4] Morgan, W. W., 2014, Collector’s Guide to Crawfordsville Crinoids, Schiffer Publishing, Limited. [5] Brosius, L., 2005, Fossil Crinoids: Kansas Geological Society. [6] Morgan, W. W., 2014, Collector’s Guide to Crawfordsville Crinoids, Schiffer Publishing, Limited. [7] Moore, R.C. and C. Teichert, eds, 1978. Introduction. In: Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part T, Echinodermata 2, Vol. 1, T7-T9. R.C. Moore and C. Teichert, eds. Geological Society of America and University of Kansas. [8] Morgan, W. W., 2014, Collector’s Guide to Crawfordsville Crinoids, Schiffer Publishing, Limited. [9] Ibid. [10] Ibid. [11] Ausich, W., 1999, Lower Mississippian Edwardsville Formation at Crawfordsville, Indiana, USA: Fossil crinoids. Edited by H. Hess, WI Ausich, CE Brett, and MJ Simms. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, p. 145-154. [12] Ausich, W. I. and Bottjer, D. J., 1982. Tiering in suspension feeding communities on soft substrata throughout the Phanerozoic. Science, 216: 173-174.