The Joe Webb People Museum at Wesleyan University has many fossils and some natural history exhibits, but it pales in comparison to the massive Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. The Peabody Museum occupies a three-story building, and has an extensive storage space for specimens in the adjacent Environmental Science building and even more at the Yale West Campus Collections Storage Center. In total, the geological-paleontological specimens at the Peabody greatly dwarf the size of Wesleyans collections, with an estimated 13 million total specimens. Therefore, the Peabody Museum is a go-to destination for learning about paleontology for people in Connecticut and beyond. According to the museum, there are about 140,000 visitors annually, an impressive number for a natural history museum. The Peabody Museum is said to be one of the world’s most well-known museums of natural history (especially for its dinosaurs), and graduate students and faculty at Yale, as well as visiting scientists, are engaged in prolific research. Therefore, this blogger wanted to learn more about the success story of this museum, and get inspiration to replicate such success, and promote our under-appreciated Joe Webb Peoples Museum. For this issue of Unseen Wesleyan, we thus went on an expedition to the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History in New Haven.

Our day started early in the morning in the Exley Science Center loading dock. We packed all our gears into the red Chevy Suburban, a signature color of Wesleyan University, and sped to the highway (I-91). The morning traffic was, on this day, not as treacherous as the waters of the Amazon River, but the congestion in New Haven almost made us late for our rendezvous at Yale University. Hurrying, we started the more unusual part of this expedition in the group of three buildings: the Kline Geology Laboratory (KGL), The Environmental Science Center (ESC) where there are museum storage and study rooms, and the Yale Peabody Museum. We walked through KGL into the connected ESC, to start our behind-the-scenes tour of the Peabody Museum.

The theme of this expedition was education, and before we started our peek in Yale’s famed museum, our faculty guide presented a talk to a group of Peabody Museum summer intern students (undergraduates and high school) on her field of research. Professor Ellen Thomas, an expert in paleo-oceanography and unicellular lifeforms, gave an introduction into general paleontology and the unicellular Foraminifera, a type of marine microorganism. She started with a discussion of taxonomy, working to debunk the oft-repeated but now outdated idea of “Five Kingdoms of Life”, going through the Domains which were popular afterwards (Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya), to end up with the (unfortunately) much more complex groupings used today, in which unicellular and multicellular Eukaryotes are combined in groupings rather than splitting Eukarya into animals, mushrooms, plants and protists. Predictably, her repudiation of the long-accepted notions of taxonomy as generally taught in high school elicited some surprised reactions from the audience. Next, Professor Thomas tackled the hard question of “What is a Foraminifer?” She covered the origins of the recognition of Foraminifera in human history, starting with a mention by Pliny the Elder (Roman Empire), first documentation in 1648 by Ulisse Aldrovandi in his work Musaeum Metallicum, and the formalization of taxonomy by Linnaeus in 1758. Professor Thomas then went on to explain the nature of Foraminifera (‘foram’ for short), extending her description from the general concept of Foraminifera as an Amoeboids with reticulose pseudopods, the shell formation types of the typical foram, to the differences between benthic (living on or in the seafloor) and planktic (floating in the water column) foraminifers. All in all, the talk was captivating in that it illuminated the not widely known subject of unicellular lifeforms in paleo-oceanography.

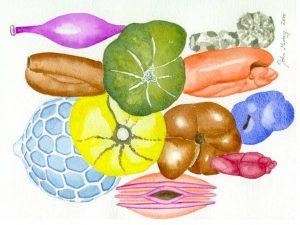

After the talk, we began our primary purpose of this expedition: investigating the success of the Peabody Museum. We started off by reviewing one of the museum’s main invertebrate paleontology archives in the ESC, which had been fitted with state-of-the-art archival infrastructure. The specimens, ranging from unicellular organisms to brachiopods and giant ammonites and bivalves, are stored in new, easily accessible cabinets, with doors that insulate the specimens from the environment. The archives are directly connected to the specimen-processing, photography and study laboratory, allowing easy access to the collections. In addition, these laboratory rooms have digitization equipment, microscopes, camera set-ups and 3-D printers, further maximizing the capacity of the museum to upload and replicate data so that they can be made available to researchers worldwide. Not only is the general storage quite easy to access for research, but the teaching specimens used for general paleontological-geological classes are ready on-demand in the facility. As we toured the storage area, we were introduced to many specimens which are valuable for studies in paleontology, ranging from pristine crinoids and Nautilus to giant ammonites and tiny Cambrian-era trilobites, and to specimen of mysterious, unidentified sponges. The expedition members were extremely impressed with the Peabody Museum’s behind-the scene operations, and greatly appreciated Susan Butts, the senior collections manager of the Division of Invertebrate Paleontology, who showed us around.

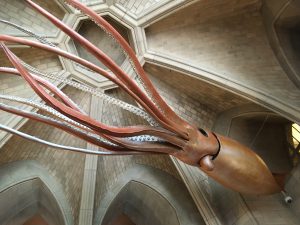

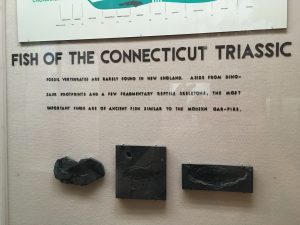

Of course, our expeditions would not have been a complete tour of the museum if we had not experienced specimens as they are shown to the public. Our team was allowed to sneak in to the main area of the Peabody Museum through the backdoor. We were greeted by a giant wall of crinoid and arthropod fossils, and a model of a giant deep-water squid hanging from the ceiling. Trekking down to the first floor, we came to a fork in the road: one way would lead to the Archaeopteryx and Paleo-art exhibition (a temporary exhibit), another to the permanent fossil exhibitions. Professor Thomas led us through the impressive hallways of Mesozoic and Cenozoic fossils, commenting on the dinosaur exhibits and the large murals. Pointing at the famous world-through-the-ages murals, she commented on the evolution of dinosaurs and plants, from the beginning of the Mesozoic through the Late Cretaceous dinosaurs and flowering plants. True to the Peabody Museum’s reputation, the exhibits of the dinosaurs – and the later mammals, also with their mural of animals through Cenozoic times – were mesmerizing. The arrangement of the dinosaurs’ bones in the middle of the hall conveyed the sense of enormity extremely well. In essence, the dinosaurs’ actual skeletons were arranged at the center of the hall, which contrasts the tiny visitor with the enormity of the dinosaurs. Moving past the main dinosaur exhibit to the other rooms, we saw that each was filled with a sense of the impressiveness of life-forms from bygone eras. From the many Ichthyosaurus to the Diplomystus dentatus of Wyoming (of which Wesleyan maintains a sizeable collection in the Joe Webb Peoples museum), the exhibition represented the paleontological worlds with great detail and pristine beauty. The team and I were greatly impressed by the Peabody Museum’s main exhibition halls.

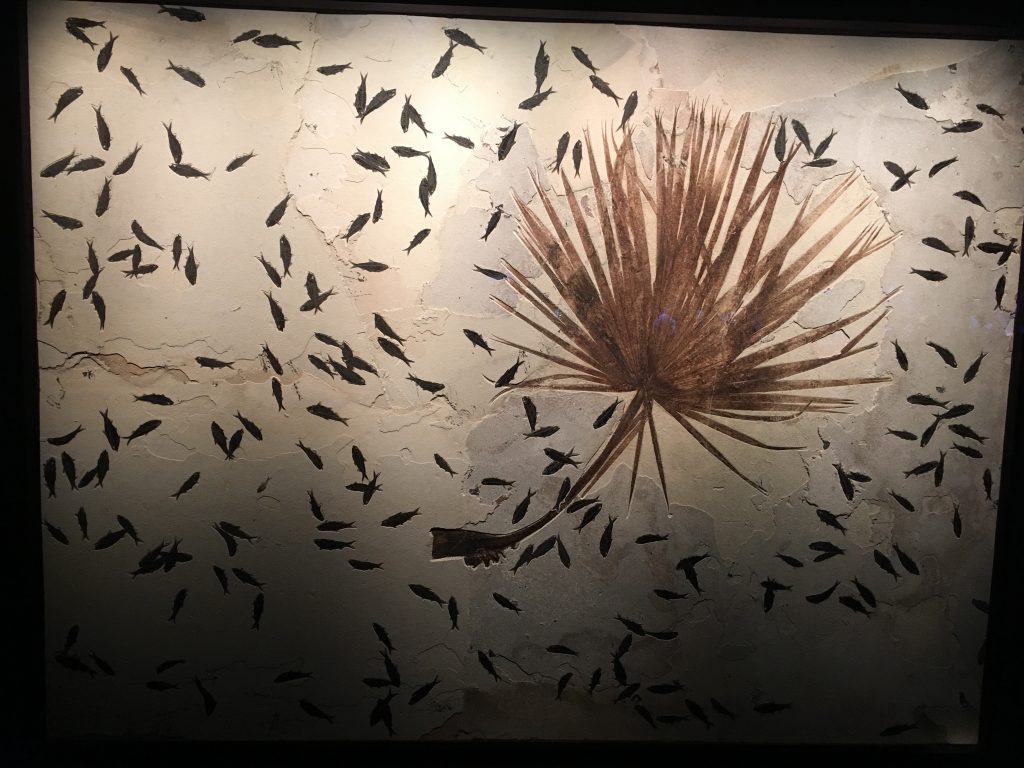

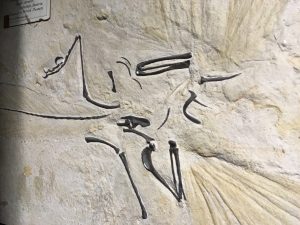

Taking a different turn at the intersection, we visited the temporary exhibition of Archaeopteryx – a type of animal which has features from small dinosaurs (non-avian dinosaurs, that is) as well as from birds (better called avian dinosaurs) – and the paleo-art created as inspired by these fossils. This non-permanent paleontology exhibition represents the interdisciplinary space between paleontology and art, showing re-imagination and recreation of Archaeopteryx and their environment, by different artists in colorful and fun ways. Due to the fact that many people still think of dinosaurs as scaly, reptile-like creatures, the Archaeopteryx – with its avian features and feathers – presents a new public education challenge for scientist and artist alike: how to show the very close family relations between ‘birds’ and ‘dinosaurs’, many of which we now know to have been feathered? The result was this exhibit: an imaginative series of artworks and creative imagination of Archaeopteryx. The artworks wonderfully educate the public through colorful illustration of various birdlike Archaeopteryx, their natural habitat, eating habits, stature, and living characteristics. We saw Archaeopteryx accompanied by fossils of other organisms: the animals had been buried in limestones deposited in shallow marine lagoons, and these limestones contain beautifully preserved fish, horse shoe crabs, echinoderms, and insects. Our Joe Webb Peoples Museum has a collection of such beautifully preserved specimens from that famous locality where Archaeopteryx was found, Solnhofen in Germany, obtained by curator S. Ward Loper through exchange of specimens with famous German paleontologist Karl von Zittel. As we walked into the exhibition, we were welcomed by artworks illustrating the evolution of Archaeopteryx into modern avian creatures. The painting replicated the famed style of Darwin’s human evolution to display each stage of transition of Archaeopteryx into modern birds.

Next, we saw an interactive illustration of various Archaeopteryx throughout the Mesozoic, simplistically explaining the various species of the creature through accessible technology. And as usual, we were amazed by the fossil specimens of the Archaeopteryx, beautifully preserved and presented by the Peabody Museum. Both of the exhibits – the Mesozoic dinosaurs and Cenozoic mammals, as well as the paleo-art of Archaeopteryx – impressed us greatly.

Our expedition to the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History gave us new insight into the function of a successful museum, and how we can cooperate to create a great center for paleontological studies. The cooperation between museums, scientists, and the public is key to create a great and publicly-appealing museum, as we saw from the talk given by our professor Ellen Thomas. In addition to visually-impressive yet educational exhibitions in the museum, organized archive and accessible collections of specimens are key to a successful museum. Armed with this knowledge, we will make the Joe Webb People Museum as great if not better than the Peabody Museum – Stay tuned!

By Sajirat Palakarn

By Sajirat Palakarn

For more information, visit: http://peabody.yale.edu/

Special Thanks to Mrs. Melanie Brigockas, Public Relations & Marketing Manager, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.