We are looking for documentation of the many fossils in the Wesleyan Collections, with much information in ancient, handwritten ‘accession books’ (dating back to the 19th century). In reading through the pages of these accession books, which in faded handwriting show which fossils were received in the Wesleyan Museum, when they came in, who collected and donated them, one sees that the collectors and donors alike were predominantly men, as judged from their names. It comes as a surprise to see ‘Clara A. Pease’, obviously the name of a woman, as donor of earth-worm material to the collections: who was this Clara Alice Pease?

Unfortunately, I could not find out much about her, but the little bit I found is quite fascinating. I found her name in the Wesleyan alumni book, as an alumna in the year of 1882. I had of course known (but did not think of it) that Wesleyan had been co-educational early on in its history, with women first admitted in 1872, but the decision to admit women was rescinded in 1909. Wesleyan was a Methodist college, and Methodism had the well-established practice of educating young men and women together. The decision to admit women reflected the efforts of important trustees, specifically Orange Judd (a Wesleyan graduate of the year 1847). Orange Judd donated $100,000.- to Wesleyan for building the hall named after him, named the Orange Judd Hall of Natural Sciences in 1871.

Scientific American (20 August, 1870) has the following text regarding the Judd Hall (which seems to imply that chemistry is a dangerous field of study):

THE ORANGE JUDD HALL OF NATURAL SCIENCE

The gift of Orange Judd, of this city, one hundred thousand dollars to the Wesleyan University, at Middletown, Conn., to found a museum of Natural History, and a school of chemistry and technology, is one of the noblest benefactions of modern times.

A few years ago Mr. Judd was a student at that college. He was a poor boy, and compelled to make his way in the world, and encounter at the outset the difficulty of finding any school in which to study the natural sciences. With rare industry and perseverance he has been able to overcome all of these obstacles, and to create for himself a fortune that he now seems disposed to devote to the good of his fellow-men.

The Museum and Laboratory is 62 feet front, and 94 feet deep, and is practically five stories high, as the basement is mostly above the surface. It is built of Portland sandstone, and is essentially fire-proof, as the cornices, doors, and window frames are of iron, and the roof of slate, and an iron and brick floor, supported on brick and iron pillars and walls, completely shuts off all fire communication between the chemical department in the first story and basement, and the natural history and cabinet rooms above. The window sashes are the only wood work exposed to fire from without, and the building is 76 feet distant from any other.

The internal arrangement of the building is in accordance with the experience of the best experts in the county.

The President of the College, Dr. Cummings, Professors Johnston and Rice, in company with Mr. Judd, and the architect, Mr. Rogers, visited the laboratories of Yale, Harvard, Columbia, Brown, and Amherst Colleges, and after consultation with the professors of these institutions, decided upon the details of the construction, and the result has been the most complete museum and laboratory to be found in the county. Such a school cannot fail to greatly add to the usefullness of the Wesleyan University, and it is to be hoped that the alumni of the College, inspired by Mr. Judd’s noble example, may be led to contribute the necessary funds towards founding the professorships required by an efficient department of natural history and technology.

Orange Judd also was the father-in-law of the first curator of the Wesleyan Museum, George Brown Goode, a Wesleyan graduate (1870) and well-known ichthyologist, who went on to become the Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian in charge of the National Museum.

Despite this advocacy by Mr Judd, clearly an influential man in Wesleyan’s history, the Wesleyan alumni records show that from 1872 until 1892, only 43 women graduated, and women thus were only a very small minority of the total number of undergraduates. As this webpage, titled ‘Wesleyan’s First Women‘ states: ‘Upon graduating, most followed the mores of the time which forced women to choose between marriage and a career. Of the forty-three who graduated, twenty-three did not marry and went into careers, usually in teaching. ‘

Clara became a teacher. I have not been able to find out much about her or her life-after-Wesleyan by googling, but she became the author of a book on general science for use in a first year course at the high school level. The title page of the book lists her as Clara A Pease of the High School, Hartford, Connecticut.

The book is titled ‘A first year course in general science’, was published in 1915 by Charles E. Merrill, and includes ‘a simple laboratory course’, with the aim to ‘Study the thing itself, not study about it’. The author ‘ makes grateful acknowledgement ..to her former teacher, Professor William North Rice, of Wesleyan University, Middletown, Conn.’ William North Rice (1845-1928) was a Wesleyan alumnus (class of 1865), a geologist, educator and Methodist minister who was deeply concerned with the reconciliation of science and religious faith. In 1867, he obtained a PhD at Yale, the first PhD in geology to be granted in the US. He was professor in Geology at Wesleyan, serving as acting president several times, and as curator for the Wesleyan Museum: the accession books show many specimens were collected by him, from Europe and the US West.

Clara’s book is available digitally online (e.g. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/60995#page/5/mode/1up, https://archive.org/details/afirstyearcours01peasgoog), and paper reprints of the book (on paper) can be bought through the publisher ‘Forgotten Books’. I found it of great interest to look at the wide range of topics covered in this book for high school (astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology and – following her own study interests from her undergraduate years at Wesleyan – geology).

The table of contents shows 26 chapters:

I: THE EARTH’S PLACE IN THE UNIVERSE; II: THE EARTH’ NEAREST NEIGHBOURS: THE MOON AND THE PLANETS; III: MATTER AND TIS PROPERTIES; IV: FORCE AND MOTION: PHYSICAL STATES OF MATTER; V: HEAT: ITS DISTRIBUTION AND MEASUREMENT; VI: LIQUIDS AND THEIR PROPERTIES; VII: PROPERTIES OF GASES, THE ATMOSPHERE, ATMOSPHERIC PRESSURE; WEATHER, WINDS AND STORMS, CLIMATE; IX: LIGHT; X: ELECTRICITY AND MAGNETISM; XI: HOW MATTER CHANGES; XII: THE COMMON ELEMENTS OF THE EARTH; XIII: SOME COMPOUNDS OF COMMON ELEMENTS; XIV: MINERALS AND ORES: THEIR VALUE AND SOURCE; XV: THE CRUST OF THE EARTH, MAN’S STOREHOUSE; XVI: CONTINENTS, OCEANS; XVII: MOUNTAINS, MINING, FORESTRY; XVIII: TOPOGRAPHIC MAPS; XIX: EARTHQUAKES, VOLCANOES; XX: RIVERS AND THEIR WORK; XXI: GLACIERS AND LAKES; XXII: LIVING MATTER; XXIII: THE LIFE OF A PLANT; XXIV: REPRODUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT OF PLANTS; XXV: THE LIFE OF AN ANIMAL; XXVI: REPRODUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT OF ANIMALS.

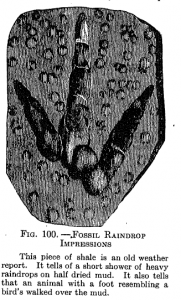

There are many figures all through the book, such as this one of what we now call a dinosaur footprint, then labeled as ‘ an animal with a foot resembling a bird’s‘ (p. 193, Chapter XVI):

At the end of the text is the Laboratory Manual, describing 31 exercises, listing necessary ingredients and questions.

Working to get our fossils documented thus thus provides interesting bits and pieces of information. Maybe we can find out more about Clara, which would helps us gain insight in how some of Wesleyan’s early women students were able to use the results of their intellectual activity as Wesleyan students later in their lives.