For many, the Connecticut River, the longest river in New England, is a serene waterway, enriching Middletown and Wesleyan University with its broad expanse of quiet waters. The main artery of the Connecticut River Valley can be traced from ‘Fourth Connecticut Lake’ in New Hampshire (with its watershed reaching into Canada) to Old Saybrook/Old Lyme in Connecticut, where it flows into Long Island Sound.

However, among the geological-paleontological community, the Connecticut River Valley – the basin encompassing the area around the Connecticut River – is also known as a prime site for fossil collection. Since the early 19th century, Connecticut has been one of the many prime destinations to study and collect local fossils, ranging from dinosaur footprints to insect tracks, from fossil fish and plants to coprolites (fossilized poo). Many famous geologists and paleontologists, from Professor Edward Hitchcock of Amherst College to Wesleyan’s own Professor Joe Webb Peoples, were part of the community gathering large collections of fossils from the Connecticut River Valley. So, we want to understand the history and evolution of the Connecticut River Valley, the reason behind the occurrence of the Valley’s plentiful fossil specimens, and Wesleyan University’s relation to the preservation of remains of the ancient Valley.

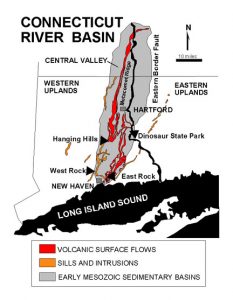

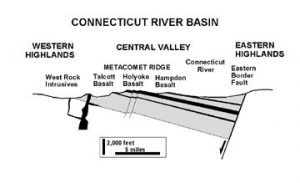

During the Mesozoic Era, which started 250 million years ago, the supercontinent ‘Pangaea’ started to split into the fragments which more or less form the present continents. This split was a violent process and did not result in clean borders of the fragments. When the North Atlantic Ocean opened late in the Triassic to early in the Jurassic (204-205 million years ago; the Triassic-Jurassic boundary is at 201.3 million years ago, large cracks formed in the Earth’s crust (one of which became the North Atlantic Ocean), and several other cracks marked places where the crust started to crack but did not open into an ocean. One of these formed in the region where we now see the Connecticut River Valley. The Earth’s crust stretched during the split of Pangaea so that several faults formed, and blocks of crust between faults could sink, forming a ‘rift valley’ (similar to the one in present-day East Africa). On the East side of the Connecticut River Valley, the Eastern Border Fault (which can be traced from Keene, NH to New Haven, CT) is the contact between the sediments that were deposited in the rift valley, and the much older rocks further to the East. Note that the Connecticut River as we know thus flows out of the old rift valley (which continues to New Haven) into the older rocks, and continues further to the East, to Old Saybrook.

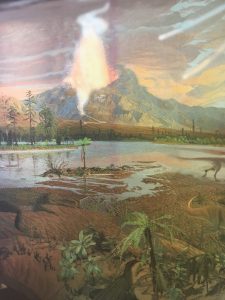

Within the sunken rift valley, which was close to the equator in Triassic-Jurassic times, sediments were deposited, in alluvial fans spreading from the Eastern border fault, and in sandstone and shale bodies, deposited in the lakes, large river bends, and floodplains, which came to dominate the surrounding valley. These water bodies became both the home and the grave of many lifeforms from the late Triassic and early Jurassic times in Connecticut. As a consequence, many of the Mesozoic creatures indigenous to Connecticut, from the various dinosaurs as known from their footprints to ancient fish and even insects, were preserved in the sediments which were deposited in and around the lakes.

In essence, some of these lifeforms (dinosaurs) left deep marks in the muddy floodplains, which then became encased in sediments after the area reflooded, as we can see in the case of Eubrontes giganteus. Countless fish died in the lakes (which suffered periods of oxygen loss), then became encapsulated by the sediments.

Wesleyan University, under the guidance of eminent curators and professors from Mr. S. Ward Loper, Mr. George Brown Goode, Professor W. N. Rice, to Professor Joe Webb Peoples, was at the forefront in preserving the old environments of the Connecticut River Valley. Beginning in the late 19th century, Ward S. Loper, Browne Good, and North Rice were instrumental in establishing extensive geological and paleontological records of the Valley. Through their collection of Connecticut River Valley fossils, they amassed an extensive selection of local specimens and displayed them to the public at Wesleyan University. Important fossils in the Wesleyan Collection are the type material of the footprint called ‘Otozoum moodii’, a footprint which is much rare than those of other dinosaurs, and which had been thought to be missing, but is in fact built into the wall of Exley Science Center (Wesleyan Collection number 183, as cited by Hitchcock in 1889). In addition, there are jaws of the rare coelacanth Diplurus longicaudatus, first described by Newberry in 1878 and collected by S Ward Loper in Durham, CT.

At one time, hundreds of Connecticut’s fossils were proudly shown (and many hundreds more preserved in the collections) in the Orange Judd Hall of Natural Sciences. In addition, Wesleyan University and Professor Joe Webb Peoples played a significant part in erecting the biggest fossil preservation area in the Connecticut River Valley, appropriately named ‘Dinosaur State Park.’ Later, Nick McDonald and Peter Letourneau contributed significantly to the study of the fossils from the Connecticut River Valley. Presently, some beautiful specimens of these priceless collections are available for all to see at the Joe Webb Peoples Museum on the 4th floor of Exley Science Center.

In addition to its beauty, the Connecticut River Valley is scientifically priceless, with its deposits of numerous delicate, beautifully preserved fossils. The formation of the rift basin during the Mesozoic era created one great condition for fossil accumulation. The sedimentary materials and the various deposits from the rift valley lakes created a perfect environment for preservation of life throughout the ages. Wesleyan University, through the leadership of great paleontologists, helped solidify the eminence of Connecticut’s paleontological credentials.

Our river has more than meet the eyes, but its present course became established only in a geological instance, after the melting of the great ice sheets which covered our area during the last glacial maximum (or ice age), about 24,500 years ago.

By Sajirat Palakarn