There is always something mystical about going underground. Since antiquity, people have always pondered the possibility of a subterranean realm – a sort of magical or hellish place right beneath our feet. In all world’s civilizations and religions, from the Greek Underworld to the Christian Hell, people have been fascinated the world’s underground. In the ancient Indian epic Ramayana – a literature this blogger read since childhood – there were verses on the many underworlds, which can range from a literal hell to prosperous kingdoms. This obsession with the esoteric subterranean civilization continues to these days, with a sub-genre of pop culture devoted to this topic. For instance, the 2008 film Journey to the Center of the Earth ostensibly captures our lasting obsession with the underworld. It is thus not surprising that some of the tunnels beneath Wesleyan, that is the tunnel systems beneath Foss Hill and Butterfield College, would generate a great deal of interest among the Wesleyan student body. While the tunnels could be freely accessed in the past, they have been sealed off for decades, and the mystique of the tunnels captures all students imagination ever since.

There were many rumors on the tunnels of the Butts and Foss Hill; one story posited that two unhappy roommates moved all of their belongings to an alcove in the Butts’ tunnel, never to return. However, another rumor caught this blogger’s attention: that there may be fossil specimens within the tunnels. As a part of the Joe Webb Peoples Museum Project, a natural history museum on the 4th floor of Exley, this rumor intrigued us and got us ready for another round of expedition. In truth, that rumor was rooted in facts, as our resident technical expert, Mr. Joel Labella, visited some of the tunnels in the past, and transported some dinosaur footprints from the tunnel to the specimen storage area many years ago. However, we were informed that there might still be fossils left behind. Thus, as is the tradition with this blogger, we went down underground to look for these for the potentially lost fossils.

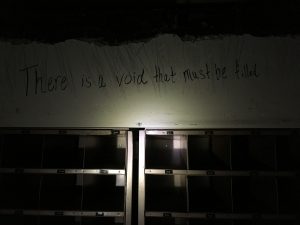

Our day started underneath the morning sun of Connecticut summer. The expedition team was checking the necessary gear for venturing into the forbidden tunnels: this included a crowbar, reliable flashlights, and a good camera for the possible emergency selfie situation. We met with our expedition expert, Jeff Sweet (facilities management) in front of a locked gate near WesShop, seemingly a harmless yet mysterious steel door. True to his credentials as tunnel terrains expert, our expert was able to produce the coveted key, allowing us to get inside the Foss Hill tunnel system. Once inside, we were greeted by with a copious amount of graffiti. Running from the ceiling to the floor, every inch of the surface area in the entrance area and tunnel was full of various murals, graffiti, and general messages, probably put in place by generations of earlier Wesleyan students. Due to our preparation and the presence of our guide, we were able to activate the light system inside the tunnel. Nevertheless, the art from the bygone eras gave us a sense of unease underlying our expedition.

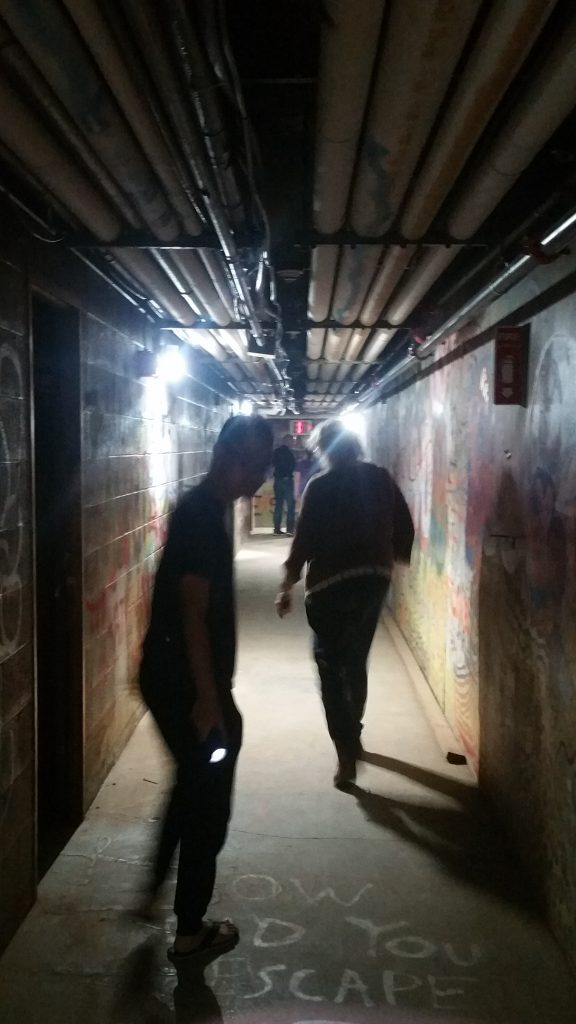

Walking deeper inside the Foss Hill tunnels, we could instinctively feel the byzantine and often claustrophobic nature of the tunnel. While spacious enough for two people to walk side-by-side, the oppressive concrete wall with many disturbing illustrations kept us a little on edge. Furthermore, certain sections of the tunnels were partially flooded, creating a picture of an enclosed and haunted tomb. As we moved onward, we were pressured to keep our eyes open for any little pieces of possible fossils, even with the ominous uneasiness. The many shadowy rooms opening off the tunnels were sometimes full of abandoned furniture and sometimes creepily empty; some were filled with an unnaturally large number of sofas, while others were left with bare concrete wall and dust-caked floor. Then, we arrived at a large room at the end of the tunnel.

The first thing that caught our eyes were a giant wooden pallet box, off to the right in the room. The condition of the box, while familiar to our experienced expedition team after our trip to the penthouse, was barely recognizable with our dim lights. Curiously, graffiti inscribed on the wall right above the box told us something crucial: “Clobbersaurus was here.” After being alerted of that fact, our expedition team began scrutinizing the box more closely. We discovered what appears to be the plaster cast of a giant shell part of the Glyptodon, whose tail we had found in the Penthouse of Exley, chronicled in our first part of Unseen Wesleyan. It was quite surprising and delightful to find another large part of the same replica thought to be lost from the records. That posed an interesting question whether more parts of the Glyptodon replica – the feet and the head to be exact –would still be stored somewhere on campus.

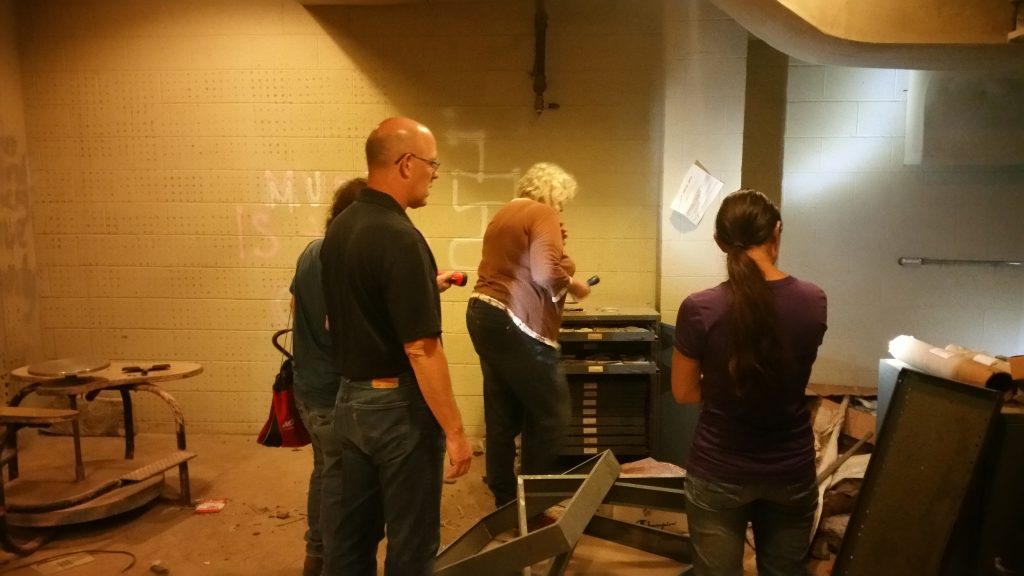

In addition to this gratifying and surprising discovery, we found two massive steel cabinets with partially broken locks. What drew our curiosity to these two archaic containers is the Ammonite-looking mural drawn near the vicinity: its existence told us that our treasure might lie inside the locked drawers. We looked over the cabinets and noted they had been fire-proof cabinets, thus possibly contained asbestos so that we could not seriously use the crowbar. This prompted our technician specialist, Mr. Joel Labella, to promise a return to the room for a more “powerful” retrieval method, to check whether museum-related paper documents might have been stored in these cabinets. We saw our discovery of the Glyptodon carapace as an early success of our expedition into the tunnels.

Exiting the Foss Hill tunnel, we set our eyes on the next target: the Butts’ tunnels. We navigated our team up the slope of the Butts into the Butthole – a silly nickname of the Butterfield College’s courtyard. Without much fanfare, we descended down the Butts C stairs into the hauntingly-lit tunnel entrance. This time, the corridor of the tunnels was much more unwelcoming, with narrow passageways and ever-present swarms of graffiti decorating the wall. Truthfully, the bright light lining the tunnels accentuated the creepy details along the route: the blinding lights cemented a sense of discomfort by highlighting every strange detail inside the tunnel, from the creepily written plea for an escape to artworks of bloody heads. The presence of locked doors dotted along the path almost plunged our expedition into paranoia, with the thoughts of someone or something being inside edging our minds. “A weak mind does not belong to this place,” the tunnels seemed to scream.

After walking a long while down the lengthy and convoluted corridors, we stumbled upon an orange-tinged room with loose wires and open stacks of servers. Whereas the jumbled mess of the deserted electrical equipment might have intrigued others, we were more fascinated by the pile of rocks, steel drawers, and a lonely steel cabinet sitting at the other far side of the room. Fascinated, we went in to investigate. It appeared to be the collections of geological specimens from Wesleyan’s own Professor of Geology, Wilbur G. Foy, professor of Geology from 1924 to 1935. Together with Professor William North Rice, he studied the geology of Connecticut. The specimens were his numbered samples indexed to the geological map of Connecticut, with various sediments and minerals comprising the drawers and the pile. Most of these historical rock specimens seemed to be discarded in disarray, which further reinforced our expedition goal to retrieve discarded specimens and collections for the museum. Wooden pallets adjacent to Foye’s geological specimen pile contained a variety of rock cores. We still do not know where or from which expedition the cores came, but they may be specimens from the core collection in the penthouse. Their quantity and even the mere existence in the tunnel suggested that there are many more treasures on campus of which we are not aware. These geological specimens, both the rocks of Connecticut and the survey cores, underscored the importance of organization and curatorship within the University’s museum; indeed, our project for the Joe Webb Peoples museum intends to provide that assistance to the Wesleyan University.

Moving on from the abandoned geological collection, we trek deeper into the abyss to search for the famed fossils underneath the Butts. The terrains we faced were certainly dangerous: we moved from corridor to corridor, room to room, crevice to crevice, and alcove to alcove. Passing countless steel gates, we walked along the narrow, copper pipes laden corridors. Taking a turn at an intersection, we again moved alongside a huge number of graffiti and locked doors. In one room, a normal-looking kitchen was vandalized by ancient arts from the legion of Wesleyan student generations. Another room was left almost untouched, saved for a makeshift table in the center of the room, giving the appearance that someone might have been here in times past. A dimly-lit bathroom, one of the many in this cavernous tunnel, gave off a tickle in the spine with its punky murals. A room we stumbled across had a set of never-played beer pong and a pile of discarded vodka bottles; bemused, we were slow to realize the weirdness of this environment: who would have set up a beer pong table in a dark tunnel, then decided not to play it? We may never know the sinister end of the players, whoever they were.

As we plunged deeper into the tunnel in search of fossils, we came across yet darker and more unsettling rooms. One room was filled with unidentified black bags and mattresses. We were told by our expedition expert that those were left behind by the janitors of the Butts, an acceptable explanation, perhaps. Walking past a brighter section of the tunnel, we were greeted by a hallway with a dusty glass wall dividing what appeared to be an abandoned underground cafeteria. It certainly looked the part, with decapitated chairs and tables, broken soda fountain, and a puzzling box of biohazard clean-up kit. The graffiti on the wall “Get to the Bunker” and “Put the lotion in the basket,” both references to a movie concerning a nuclear apocalypse and serial killer respectively, seemed to imply the reason behind this cafeteria’s closure. Reaching the end of the tunnel, one fact became apparent to us: despite our extensive search for the fossil, we failed to find the rumored Butts’ fossils in this expedition. Except for our notes on the geological collections, we sadly returned empty-handed.

While not all our expeditions yielded a significant number of fossils, the specimens we found were no less important to the museum and Wesleyan University. The Glyptodon replica was once a part of the historic Orange Judd Museum of Natural History, an institution of Wesleyan University since 1871. When the museum was closed in 1957, the Glyptodon, along with many valuable fossils and specimens, were thought to be lost forever; that is until now. With closer analysis, we might even discover something far more important with regards to the geological collection underneath the Butts. The pieces and collections we found are the fabric of Wesleyan itself. Thus, as a proud Wesleyan student and a lover of everything history, I cannot appreciate the Joe Webb Peoples Museum enough.

By Sajirat Palakarn

By Sajirat Palakarn

Special thanks to Mr. Jeff Sweet, Associate Director of Facilities Management, Wesleyan University, and Yonathan Gomez ’18