If there is a hashtag that defines museum practices of the 21st century, it’d better be #digitization.

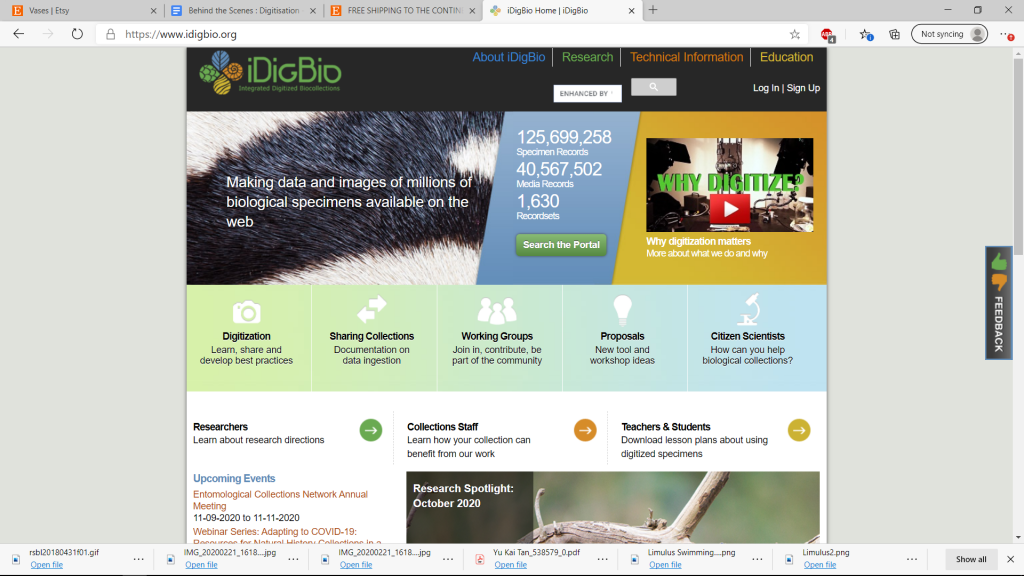

With the leaps and bounds computing power has taken in the past decade, researchers have been getting on the ramp of creating large online biodiversity databases for collection objects. An example is the Integrated Digital Biocollections (iDigBio) is an international collaborative to create a large public depository of biodiversity data for research, teaching, learning, citizen science, conservation and more.

After years of negotiations and planning, Wesleyan has jumped on the bandwagon at long last. We have now set up an online iDigBio-compatible Specify7 database system to digitize our biological and paleontological collections. A huge shoutout to ITS for funding the database platform. In a historically short semester, this progress has allowed us to modernize our collection practices, to begin to make the Wesleyan collections known to the international scientific community, and provided an avenue for students to gain hands-on, in-person and remote curation experience.

Over this semester, Andy Tan’21 and I have helped set up and trained the museum crew on the intricacies of the sophisticated relational database. We learned the ropes for Specify during our internship in the Paleontological Research Institution in Ithaca NY during summer of 2019, supported by the College of the Environment Summer Research Grant and Gordon Career Center Summer Experience Grant.

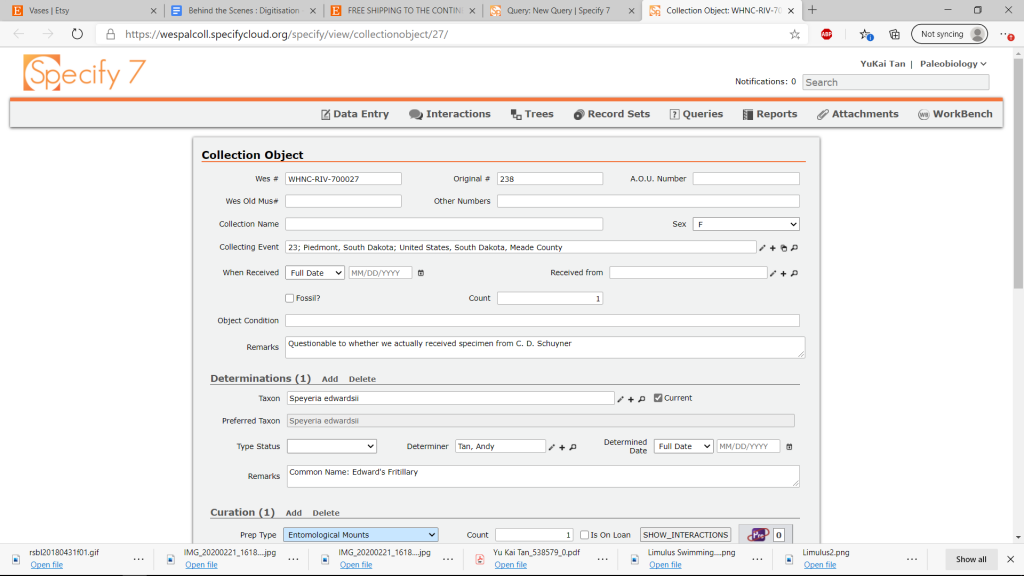

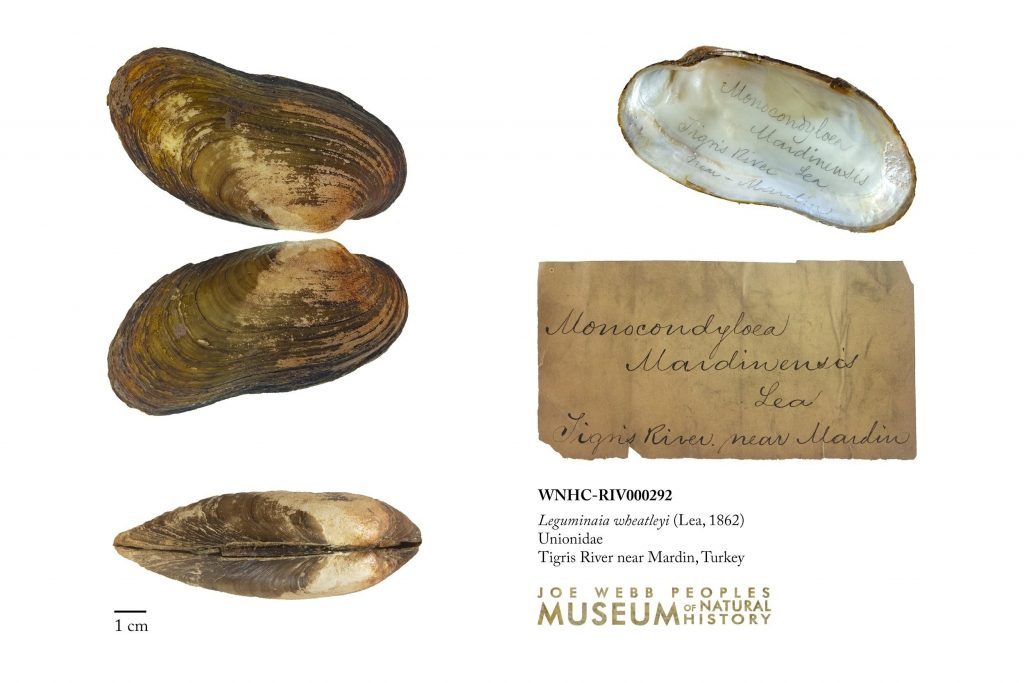

Digitization of our specimens has begun in earnest on different collections with different student and faculty curators; Fletcher Levy ‘23 is digitizing the osteological collection; Margaret Fitch ‘22 who is a remote student this semester, is digitizing the butterfly collection with on-site help from Andy; Dr. Ann C. Burke is digitizing the bird taxidermy collection using metadata collected by generations of students’ work from Camille Britton ’20, Mai-Anh Tran’20 and Wisly Juganda ’20; I am digitizing the freshwater mussels collection. To date, we have digitized 200 objects, with many more to come, including objects in paleontological, spirits and bird egg collections.

Digitization is an onerous process. Each specimen can take a cataloguer up to an hour. The specimen needs to first be identified using an old label, entry in an accession book, a key or publication. Metadata such as donor, collector, date of collection, locality, preparation, number of specimens, old label information, exhibition history also need to be obtained and verified from archival documents and compiled. The cataloguer then assigns a new Wesleyan institutional number, inputs each bit of information into the database, and creates a set of meaningful (and awfully complicated) relationships between each piece of information — the hallmark of a powerful relational database. High-quality photographs (and/or 3D scans) of specimens are taken of as many specimens as feasible, with a scale bar and color checker, then uploaded to the database.

Digitization is more than a catalogue for in-house inventory purposes. The digitization of small collections opens up the prospect of international collaboration.

Since humans began collecting natural specimens, specimen data is often kept in written museum ledgers that are not searchable. With online databases, researchers can search online digital databases of collections to decide which institutions they intend to visit for research. Analytical research using available online data instead of direct access to physical specimens is also possible through digitization, making it possible to address new questions with big data. For instance, in the EPICC (Eastern Pacific Invertebrate Communities of the Cenozoic) Project funded by the NSF to digitized Cenozoic fossil marine invertebrates on the US Pacific Coast, 23 times more localities were identified than previously known from publications and other databases (from 1,139 to 26,059 known sites).

Publications that figure or cite collection objects bring the collections into public scientific discourse. This renders scientific value and much-needed publicity to small collections such as ours, often dismissed by funding agencies as “teaching collections”.

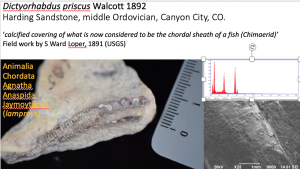

Even small (relatively speaking) collections such as Wesleyan’s more often than not house scientifically important specimens. In my research of the freshwater mussel collections, I have identified two specimens as type specimens. Type specimens are important since they are THE specimen designated by the discoverer or original author of the species to define the species. Our Smith Curator of Paleontology, Dr. Ellen Thomas has previously identified paratypes of the middle Ordovician Dictyorhabdus priscus Walcott from Canyon City, Colorado in our collections. The collection of the specimens was documented in the publication by famous palaeontologist Charles Doolittle Walcott, with field trip details in the Smithsonian archives, but knowledge of the whereabouts of Loper’s specimens was lost for over a century[i]. During the 2019 Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections conference, her presentation garnered significant interest, and researchers who have been searching for these type specimens congratulated her on the rediscovery.

Curator Samuel Ward Loper also collected amazingly preserved fish and plants from the middle Eocene Green River Formation (Wyoming) and insects and plants from the late Eocene Florissant Formation (Colorado) in the 1890s, and these collections have never been formally described. Who knows what unknown species are stored here at Wesleyan? Our digitization efforts will make these collections known to the international paleontological community.

No doubt, there are many more important specimens in our collections waiting to be found. A digitized collection will greatly enhance our collections’ role in scientific research and discourse internationally.

The funding for specimen digitization is only a small portion of overall resources already allocated to collection curation and maintenance, but the funds allocated promises an excellent yield on the investment in museum science worldwide.

Soon, the world will connect with us through our online database. The potential is incalculable!!

______________

Notes:

[i] Walcott thought these were among the most ancient vertebrates in the world, but there was major disagreement on what these mysterious looking objects were, with scientists arguing they were cephalopods (squid relatives) or even sponges. Wesleyan students used the Scanning Electron Microscope to establish that the fossil material was not calcite, as it would have been if these specimens were cephalopods or sponges, but apatite (calcium phosphate), establishing that these were indeed vertebrates. Nowadays, they are tentatively assigned to vertebrates, related to jawless fish (lampreys). Wesleyan curator Samuel Ward Loper collected these specimens while in the field with Walcott in 1891 while both were employed by the US Geological Survey.