Our tireless obsession to name and categorize things into categories with impermeable and immutable boundaries is perhaps one of our species’ peculiarities: assigning categories to the numerous and diverse forms of life on Earth can be seen as somehow giving us assurance, in creating an illusion that we may be dominant and in control of species on Earth.

In this exhibit, we strive to make the strange familiar and the familiar strange, by showing modern concepts of relations between groups of animals, which contrast with concepts that became established in the late 1800s, the time of establishment of collections in Wesleyan Natural History Museum, and to which many of us are still, erroneously, accustomed.

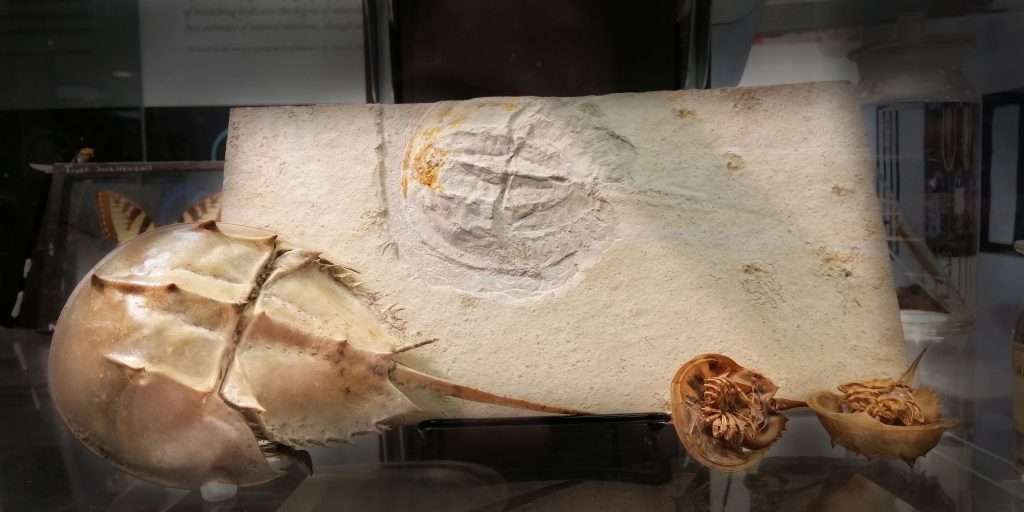

For instance, star fish (sea stars) and sea urchins are displayed next to humans and bats, to drive home the point that they are in fact, far more closely related to vertebrates than to corals or worms. Some living fossils are on show, the most staggering of which is the horseshoe crab, with the modern variety next to a 150 million year old fossil (Jurassic). They really haven’t changed that much in how they look!

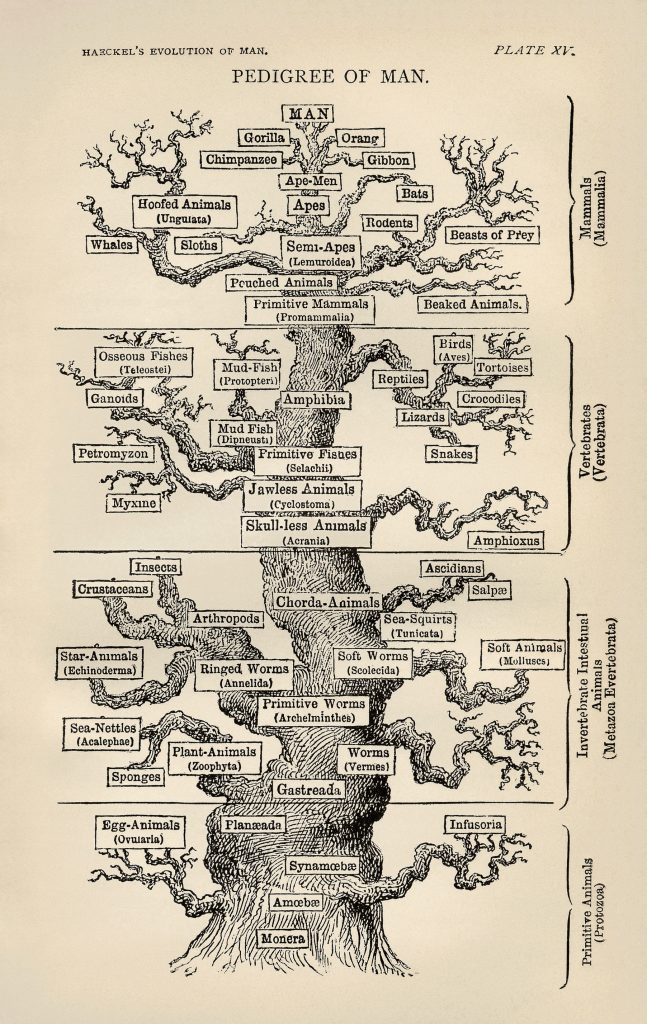

Modern concepts are to a large extent based on genetic (thus family) relations, as shown in the ‘Tree of Life’ that greets the visitor at the front of the exhibit, rather than on external morphology (how things look), as shown in Haeckel’s ‘Tree of Life’ (1879) on the wall behind the exhibit.

The modern ‘Tree of Life’ is based on genomic analyses, and shows that more than two-thirds of the genetic and chemical diversity of Earth’s life forms is within single-celled Bacteria and Archaea, with small cells without a nucleus (prokaryotes). Humans, plants and mushrooms, as well as one-celled organisms with a complex cell with a nucleus (Eukaryotes) share a few inconspicuous branches on the lower right side of the tree: the living world consists mostly of very small but extremely variable and complex organisms.

However, bacteria were not quite appreciated as complex, diverse and ubiquitous at the time when our natural history collections were made, owing not only to the technological difficulties of collecting bacteria in the 19th century, but also – more importantly – to the fact that they hardly can be exhibited, and lack that inspiration of the awe of nature, relative to large, much more ostentatious animals. Our exhibit showcases animals, fungi and plants from our collections that by themselves, despite representing an infinitesimally small part of global biological diversity, document a vast array of body plans, sizes and diversity.

However, bacteria were not quite appreciated as complex, diverse and ubiquitous at the time when our natural history collections were made, owing not only to the technological difficulties of collecting bacteria in the 19th century, but also – more importantly – to the fact that they hardly can be exhibited, and lack that inspiration of the awe of nature, relative to large, much more ostentatious animals. Our exhibit showcases animals, fungi and plants from our collections that by themselves, despite representing an infinitesimally small part of global biological diversity, document a vast array of body plans, sizes and diversity.

On the wall behind the exhibit hangs a reproduction of a Tree of Life, published by the evolutionist fan of Darwin, and scientific illustrator Ernst Haeckel in 1879, a testimony of the anthropo-centric and human observation-centric mode of science, filled with large beautiful animals that we can easily detect with our unaided senses. It also speaks to a then popular social theory, in which it is believed that complex forms evolved from simpler forms in an uninterrupted linear fashion, the ultimate perfect form of which is represented by European man within the group of Mammals, at the top of the tree.

The entire Wesleyan campus is erupting in a celebration of biodiversity, and our changing views of the human position within it. Audible Bacillus at the Ezra and Zilkha Gallery explores interspecies relationships between us and bacteria, while Bestiary in the Davison Art Centre showcases a history of representation of animals in art. Join in the conversation and rediscover your place in the complexity of biodiversity.