The natural world is not always generous in revealing its wondrous secrets. From the crystals buried in the depths of the Earth to the star fields behind distant dust clouds, the wonders of nature are often obscured from direct access by people striving to obtain knowledge. It is even more frustrating when such secrets are concealed in an object within the grasp of our fingers, rather than in remote regions of our universe.

Dissecting an important specimen to see what is beneath its skin may destroy the specimen. Luckily we can – without destroying animal specimens – look at their insides with relative ease using clearing and staining methods.

Clearing and staining is a useful tool to observe internal skeletal structures of animals to help us understand how an animal moves, providing insight in the link between form and function. When Wesleyan Biology Professor David Bodznick retired, he left a gift to the natural history museum collections – the first of its kind for many years: three Little Skates, Leucoraja erinacea (Mitchill, 1825). Meat from these skates has become popular in culinary arts, as an economical replacement for the more expensive scallops.

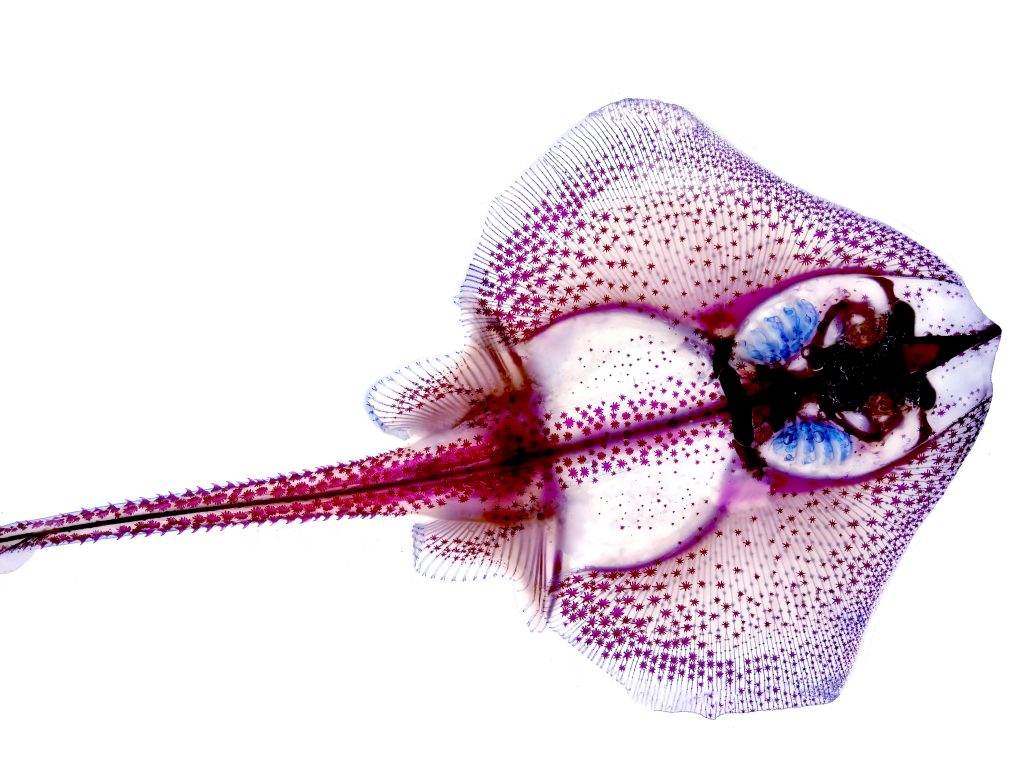

Skates have no bony skeleton, belonging to the group of cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes) that includes sharks and rays. We embarked on a week-long journey of preparing them for visualization of their skeletal system, then waited 6 months for them to clear.

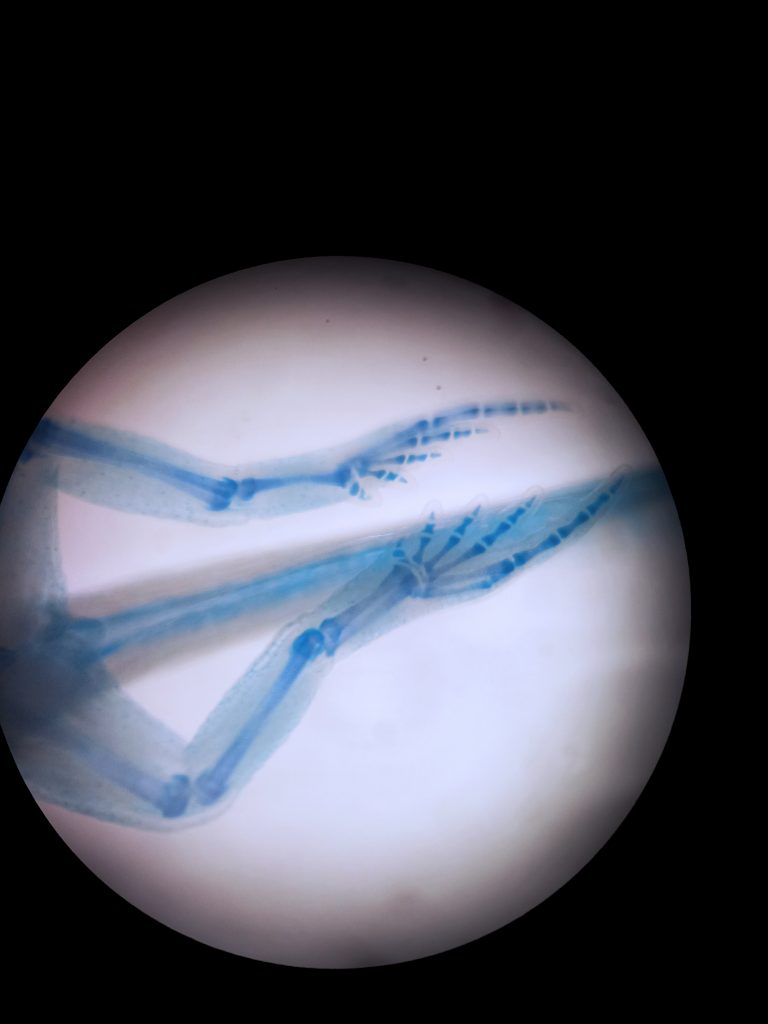

Even though the name of the process appears to be self-explanatory, the actual process of clearing and staining is somewhat magical to see, as the results unfold before one’s eyes. We first put the preserved skates in a pungent solution of acetic acid and 70% ethanol, to which Alcian Blue had been added in order to selectively stain cartilage. After a day, the skates were thoroughly rinsed. A stained skeleton is not very useful unless it can be seen, which is achieved in the ‘clearing’ step of the process. Trypsin is an enzyme that removes all proteins from the soft tissue except collagen, which holds the soft-body in place. After maceration in trypsin, the skates are ‘cleared’, appearing translucent.

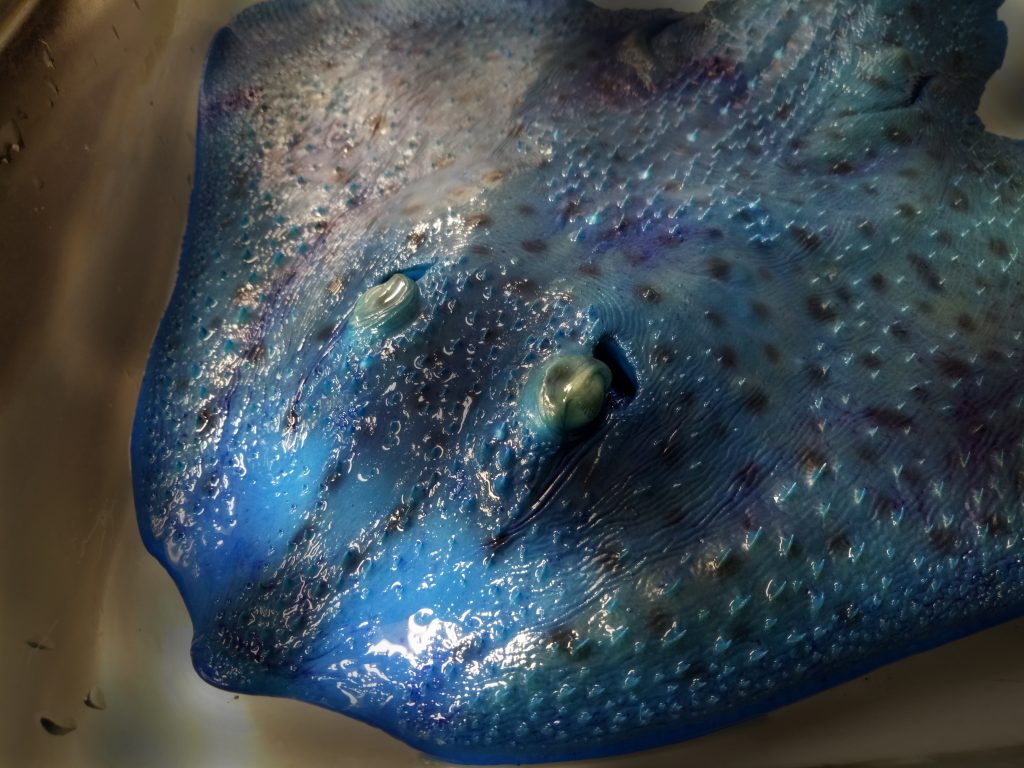

Alizarin red is a selective stain for calcium-containing tissues. The cartilaginous skeleton of skates calcifies as they age, though not transforming into true bone. Skates have beautiful, star-shaped scales embedded in their skin. Both scales and calcified skeletal elements stain red with Alizarin red. We soaked the skates in this dye for 24 hours, to label any calcified tissue present, then further cleared the soft tissue by bleaching with potassium hydroxide and small amounts of hydrogen peroxide, which is a potent oxidizing agent commonly used as antiseptic, or (at lower concentrations) a teeth-whitener. When the bleaching was complete, the skates appeared milky white, with the stained skeleton visible throughout. To enhance the transparency of the skates, we put them in glycerol, which has a refractive index very similar to that of collagen, rendering the skates wholly transparent.

The end result is not only visually stunning, but also preserves all skeletal material in place, as it was in the living organism, and thus improves on visualization techniques such as X-rays and electron micrographs, which do not preserve the three-dimensional movement of skeletons encased in soft tissue. Even MRI cans cannot attain the resolution of clear-and-stain specimens. Ultimately, this is an inexpensive and straightforward technique to prepare and observe them.

We invite you to indulge in the bizarre experience of gazing into the depths of transparent animals as we exhibit them in temporary exhibits around the Wesleyan campus.

Cover photo: Eye of the Little Skate, Leucoraja erinacea (Mitchill 1925) from Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Gift of Professor David Bodznick.