Long thought to be marine dinosaurs, Plesiosaurs and Ichthyosaurs were once formidable apex predators in the Mesozoic. Living in oceans at the same time when the dinosaurs were roaming the land, these magnificent beasts are now iconic displays in many major museums, showing these animals as representatives of this golden age of the giants, some 228 to 112 million years ago (Ma). Their discovery is a story about an unsung woman of science, whose contribution to palaeontology changed our understanding of evolution forever.

It is a story of heartbreak as well as classist and elitist struggle, which lies behind that innocent, lighthearted children tongue-twister derived from Terry Sullivan’s lyrics to a 1908 song.

She sells seashells on the seashore

The shells she sells are seashells, I’m sure

So if she sells seashells on the seashore

Then I’m sure she sells seashore shells.

The she was Mary Anning (1799-1847), born poor in southern England, and was never far from the austerity that she internalised as a way of living. Being a woman in the household of a low-class cabinetmaker, Mary had no access to formal education. She did, however, accompany her father in the unusual pastime of fossil hunting along the coast of Lyme Regis, and their fossil finds were sold as curiosities. Neither of her father’s occupations improved the circumstances of the family, and when the father died in 1810, his pregnant wife was left with little more than a large debt.

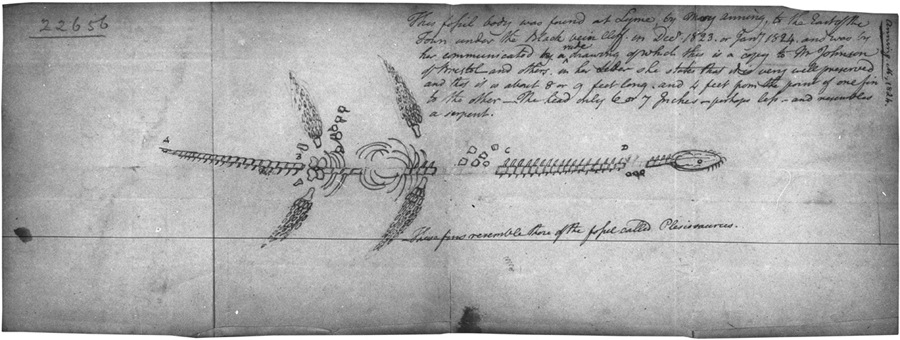

It was Mary who found her way in the world by continuing her father’s work in fossil hunting and turning it into a livelihood.With her widowed mother, she managed a little fossil shop by the sea to eke out a meagre income. In 1811, she made one of the most significant fossil finds in all of history. On the coast of Lyme-Regis, she co-discovered an Ichthyosaurus with her brother – the first of its kind ever to be discovered. This gargantuan specimen was soon purchased by a private collector for £23 (approx. $2200 in today’s worth). In subsequent years, she became the most prolific fossil hunter of her time, unearthing many other important fossils including Plesiosaurs, Pterodactyls and more Ichthyosaurs, many of which eventually became important holotype specimens.

Nevertheless, being a working class woman in the 19th-century, Mary never had much credibility in the scientific community. Despite her frequent correspondence with many of its prominent members, and despite providing fossils for their research, she was always the daughter of a cabinetmaker that had no place in scientific discourse. A series of 6 papers starting in 1814 by Sir Everard Home described the Ichthyosaurs based on Mary’s finds, but she was not credited in the papers. Similarly, in 1821 and 1824, William Conybeare published and presented descriptions of the Plesiosaur fossils and thanked the collector of the fossil, but failed to mention Mary in any way. Even Sir Richard Owen- the scientist who coined the term “dinosaurs”- neglected to mention this lower class woman, despite having thanked the gentleman who acquired it from her, when he described Plesiosaurus macrocephalus in 1840. So harshly unjust was their negligence of her contributions that she once lamented in a letter “The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.”

The Plesiosaurs and Ichthyosaurs she introduced to science were the most terrorising predators in the oceans during their heyday. Growing to 15-20m in length and weighing almost a tonne, these monsters were powered by strong flippers that allowed them to pursue their prey at remarkable speeds. Ichthyosaurs were so successful in their survival strategies that they survived for almost 120 million years. By the Cretaceous era, they had adapted to living in every ocean on the planet. Their discovery marked one of the most pivotal moments in palaeontology at a time when the issue of extinction – whether God’s divine creations could possibly become extinct – was a matter of great contention, their discovery was the final testimony that extinctions do occur. When living counterparts of tiny fossil seashells and trilobites may be argued to still be lurking somewhere in the unexplored depths of the ocean, some unfortunate fishermen would almost inevitably have encountered giant swimming lizards should they still inhabit our oceans.

With contemporaries like Darwin, Charles Lyell and Richard Owen, Mary’s story may have been drowned in the many unjust traditions of scientific publications in the 19th century. Nevertheless, the drama that evolves around her life’s work will live on on Wesleyan’s walls and that of many major museums, as a testimony of science as a field where success in expanding knowledge triumphs over other qualities.

Marvel at the grandeur of these impressive monsters, and listen to their bittersweet tales of toil and tears of an unforgotten giant– Mary Anning. Soon to come, on the 3rd floor of Exley…

Cover photo: Ichthyosaurus platyodon skull detail, copy of an original found by Mary Anning, in the Joe Webb Peoples Museum Collection at Wesleyan University. Photo courtesy of Andy Tan ’21.